Preface – The Story of Eastern and Western Astrology

In this article, we delve into the fascinating world of astrology by exploring the two primary zodiac systems: the Sidereal Zodiac, integral to Eastern Vedic astrology of India, and the Tropical Zodiac, foundational to Western astrology, with origins in ancient Greece and Babylon (modern-day Iraq). This topic is a source of considerable debate among astrologers, mainly because the Tropical Zodiac does not align with the actual positions of celestial bodies.

The Tropical Zodiac maintains a strong presence in Western popular culture, yet it often leads to confusion when individuals discover its astronomical inaccuracies. Many Western astrology enthusiasts begin their journey with the Tropical Zodiac due to its widespread recognition. However, as they deepen their understanding, some find the discrepancies unsettling. Despite this, the Tropical Zodiac continues to hold sway over mainstream consciousness, even as a growing number of Western astrologers transition to the Sidereal system.

What is widely accepted does not necessarily equate to being truthful or precise. This is reminiscent of the not-so-distant past when the prevailing belief was that the Earth was the centre of the universe, with all celestial bodies revolving around it. Any framework built upon shaky premises is destined to crumble, as we will explore in the future implications of the Tropical Zodiac. In contrast, those ideas grounded in a solid foundation of truth and accuracy endure over time, much like the Sidereal Zodiac.

This three-part article aims to unravel the story of Eastern and Western astrology by examining the foundational principles behind these two systems. We will scrutinize them through various lenses, including historical, philosophical, astronomical, and futuristic perspectives, among others. Join us as we embark on this enlightening journey to better understand the zodiac and its profound impact on human culture and consciousness.

Part I Overview

In Part I of this exploration of the Sidereal and Tropical Zodiac, a journey through time and space begins, tracing the origins and evolution of astrology from ancient civilizations to contemporary practices. This segment delves into the profound human connection with the cosmos, starting with the earliest stargazers who looked to the heavens for guidance and meaning.

The journey begins with an exploration of the three cradles of civilization: the Indus Valley, Mesopotamia, and Ancient Egypt. These cultures established the foundational stones of astrological traditions that profoundly influenced later societies, including ancient Greece and the Hellenistic period. As we navigate these historical landscapes, we will delve into how astrology permeated various cultures, revealing the differences between Eastern and Western philosophies.

The cultural philosophies that cradle these traditions provide essential context for their unique astrological systems.

This segment includes a fascinating account of Alexander the Great meeting the Indian sage Kalanos, symbolizing the clash of Eastern and Western thought. We will also delve into “The Two Systems and The Two Clocks,” exploring how these frameworks developed into distinct legacies.

In the final section of Part I, we delve into the essence of the roots of knowledge and its sources, particularly within the realm of astrology. Additionally, the section explores a harmonious approach by integrating the Sidereal zodiac into Western astrology, urging a reconnection with the cosmos. By lifting our gaze back to the heavens, we honour the wisdom of our forebearers and acknowledge our intrinsic connection to the universe, reminding us that we are all part of a grand cosmic narrative.

The Ancient Stargazers: Early Human Connection to the Cosmos

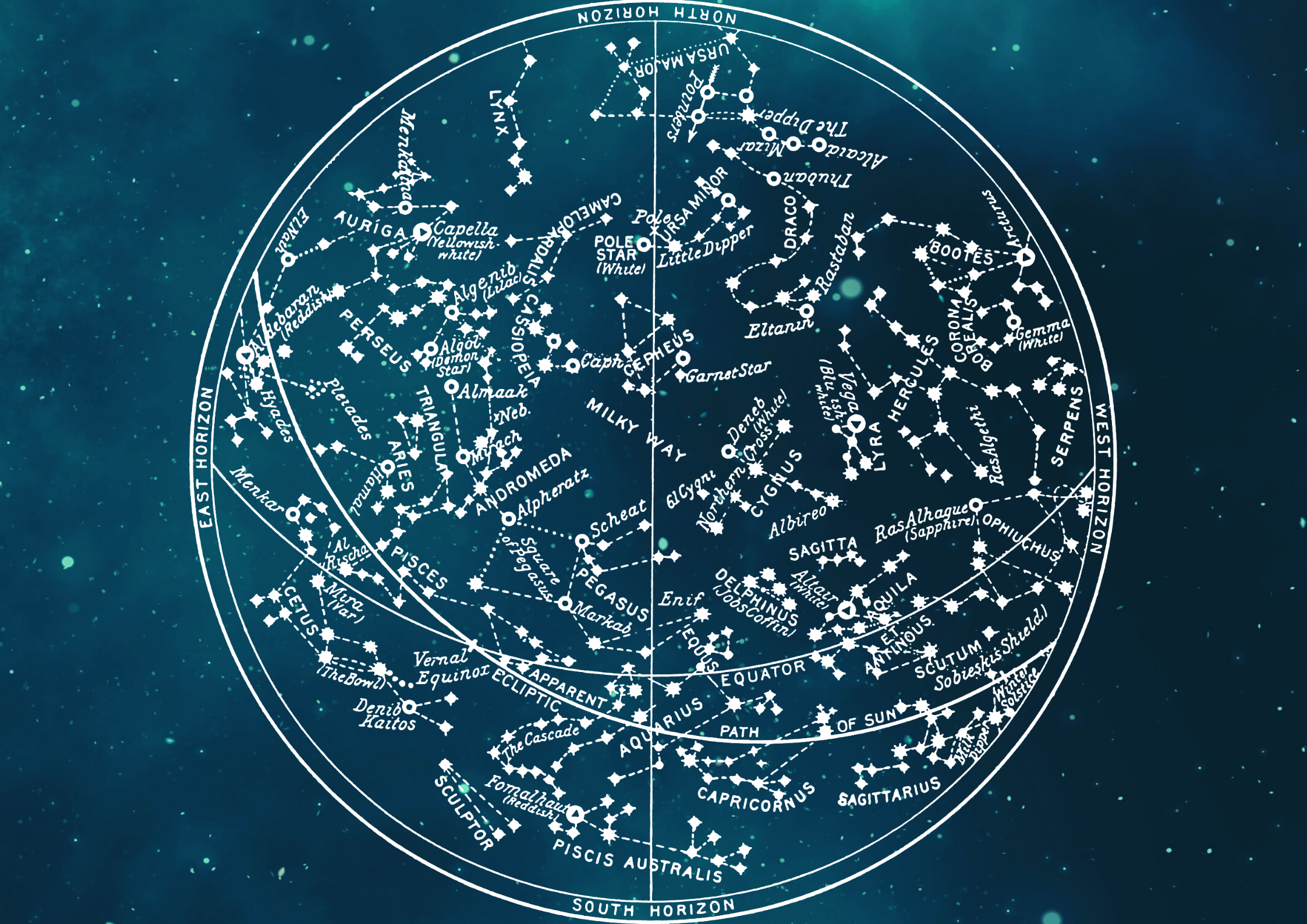

Under the vast expanse of the night sky twinkling with stars, early humans huddled together, their eyes captivated by the shimmering spectacle above. The Milky Way stretched out in a breathtaking display, each constellation like a silent storyteller whispering secrets of the universe. The clear skies, untouched by pollution, offered an awe-inspiring view that filled them with wonder and curiosity.

Ancient humans, with their eyes turned skyward and feet firmly planted on the soil, exhibited a profound relationship with the cosmos. As they observed the heavens, they began to notice patterns – the waxing and waning of the moon, the steady march of the stars across the night, and the sun’s path that governed their days and seasons.

Elders would recount tales of how certain stars foretold the migration of herds or the coming of rains, passing down these celestial stories through generations. As hunter-gatherers transitioned to agricultural societies, understanding the sky became even more crucial; the position of the sun and the appearance of certain stars marked the time for planting and harvesting. Without the aid of modern telescopes or sophisticated technology, they relied on their keen observation skills and a deep sense of curiosity to understand the night sky.

These celestial patterns were more than just distant lights; they were guides, teachers, and timekeepers. The stars became their compass, the sun their clock, and the moon their calendar.

Through this cosmic dialogue, ancient humans developed a keen understanding of their environment, allowing them to cultivate the land, harvest its bounty, and sustain their communities. In this way, the universe was not a distant, indifferent expanse but a close, intimate partner in the journey of human existence.

The profound connection between celestial patterns and earthly events birthed early astronomy and astrology. As ancient observers meticulously tracked the heavens, they uncovered a cosmic rhythm that echoed the very cycles of life, intertwining the movement of the stars with the destinies of humankind.

The Cradles of Civilization: A Glimpse into Ancient Societies

The story of human civilization is a relatively recent chapter in the long history of our species. While humans have roamed the Earth for millions of years, the first civilizations emerged only a few thousand years ago, marking a significant leap in human development. As humanity transitioned from nomadic lifestyles to settled communities, the foundation was laid for the emergence of complex societies.

In the nascent stages of human history, three magnificent civilizations—the Indus Valley, Mesopotamia, and Ancient Egypt—rose like shimmering jewels along the lifeblood of river valleys. These cradles of civilization, nurtured by the Indus, the Tigris and Euphrates, and the Nile rivers, wove the first chapters of our shared human story. Each one blossomed with ingenuity, culture, and the spirit of a people driven to create wonders that still echo through the ages.

Indus Valley

Nestled within the Indian subcontinent lies the heart of one of the world’s most ancient civilizations—the Indus Valley Civilization. Flourishing between 3300 and 1300 BCE, this civilization was a beacon of urban sophistication and architectural mastery.

Cities such as Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro were meticulously planned in a grid pattern, showcasing an advanced level of municipal organization and an intricate drainage system that remains impressive to this day. The brilliance of these cities reflects not only the ingenuity of their inhabitants but also the profound cultural and spiritual foundations they established.

Transitioning from architectural marvels to spiritual depths, the term ‘Hindus’ originates from the people living around the Indus River. Originally, ‘Hindu’ was not a religious designation; rather, it was a geographical term used to describe the inhabitants of the region surrounding the Indus River.

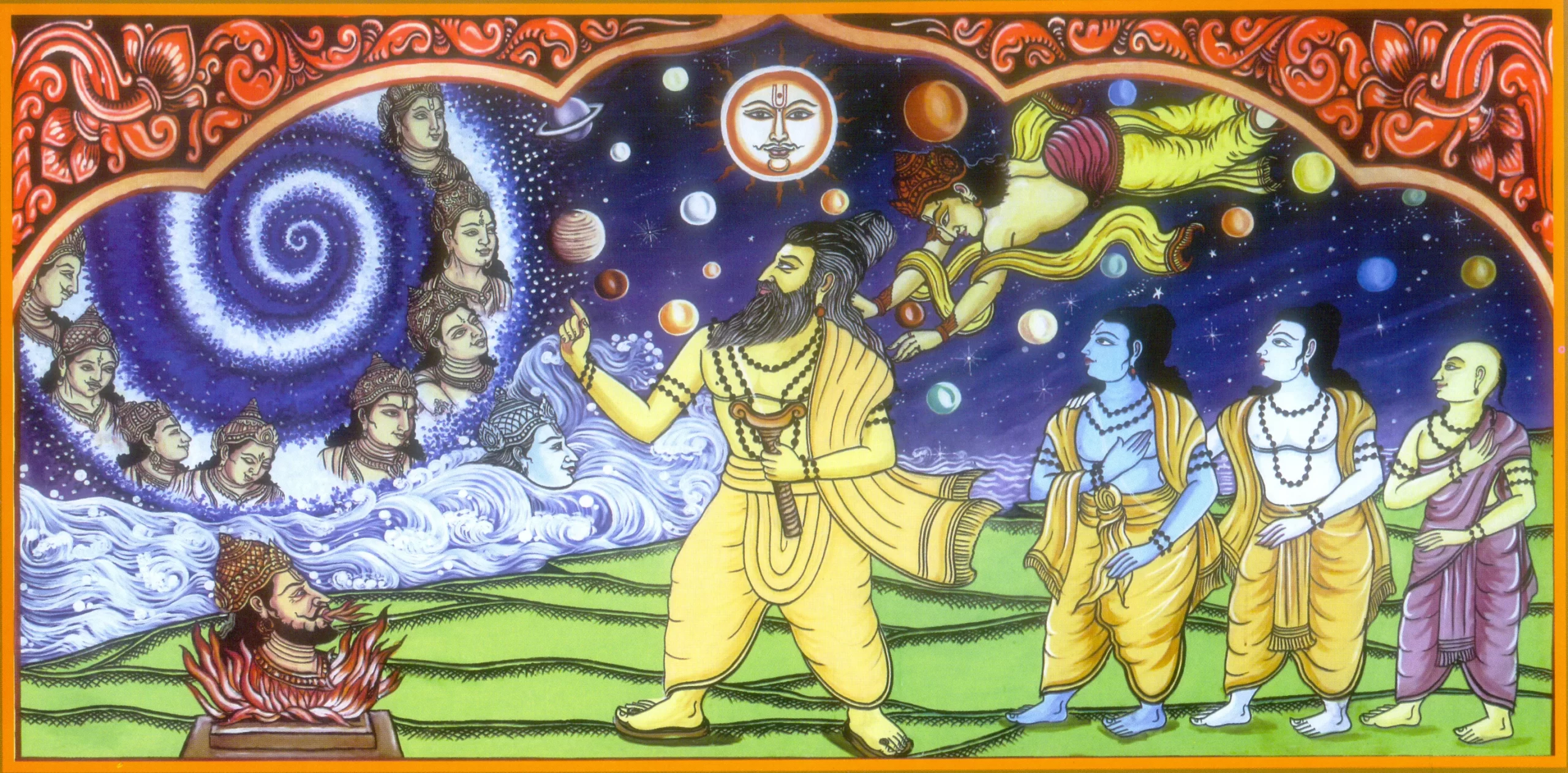

This civilization laid the groundwork for various cultural and spiritual traditions that followed, including the divine treasure of Vedic astrology. Believed to be over 5,000 years old, Vedic astrology has its roots in Ancient India and stands as divine knowledge bestowed upon humanity. This ancient science of the stars was developed by the sages and seers of the Vedic period, who meticulously observed celestial phenomena to uncover the mysteries of the cosmos.

This celestial wisdom, rich and profound, was initially transmitted orally for generations before being committed to writing. The sages’ dedication ensured that this sacred knowledge, with its deep understanding of the universe, was preserved for future generations.

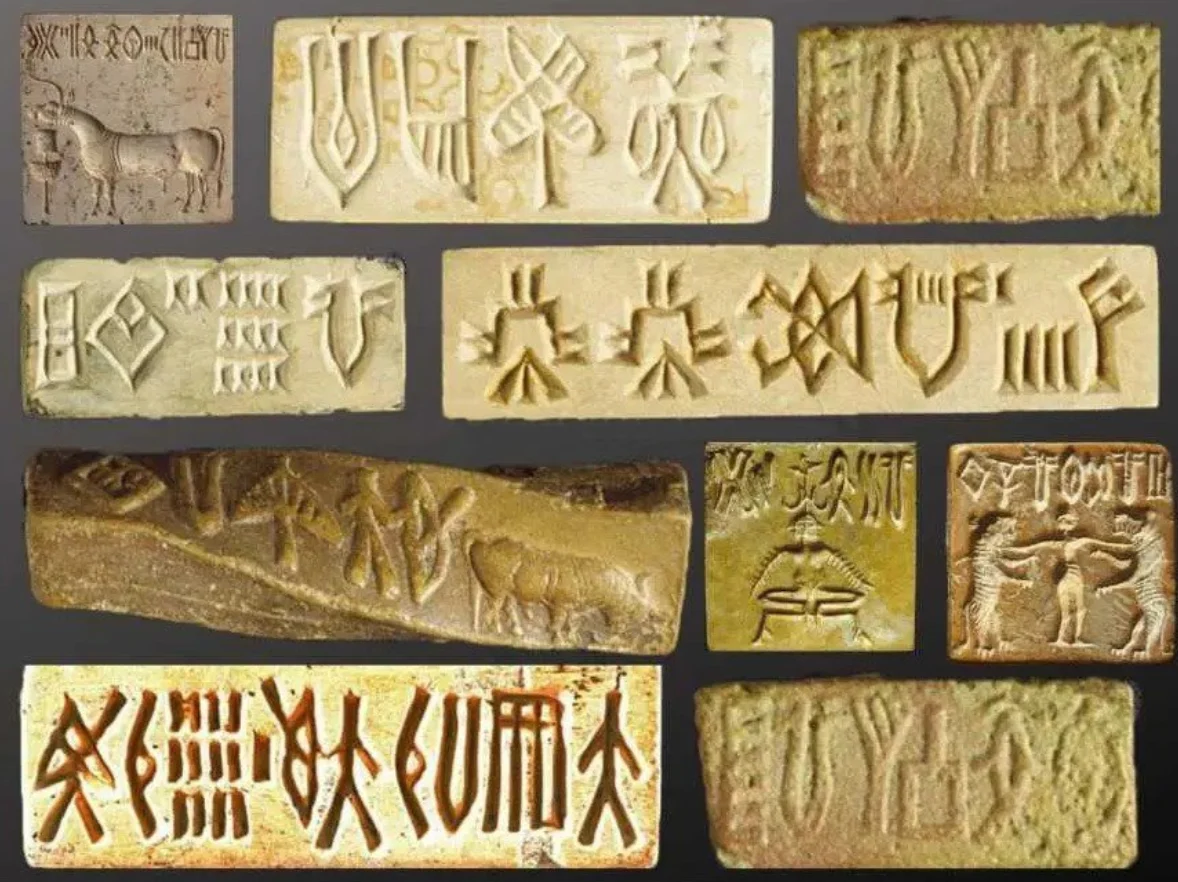

Even with the advances in modern technology, the enigmatic Indus script, with its array of symbols and pictographs, remains undeciphered. This script, which adorns seals, pottery, and tablets, continues to whisper the secrets of a civilization still shrouded in great mystery. Despite extensive research and even the application of artificial intelligence, the true meaning of these ancient symbols eludes us, leaving one of history’s greatest puzzles unsolved.

Mesopotamia

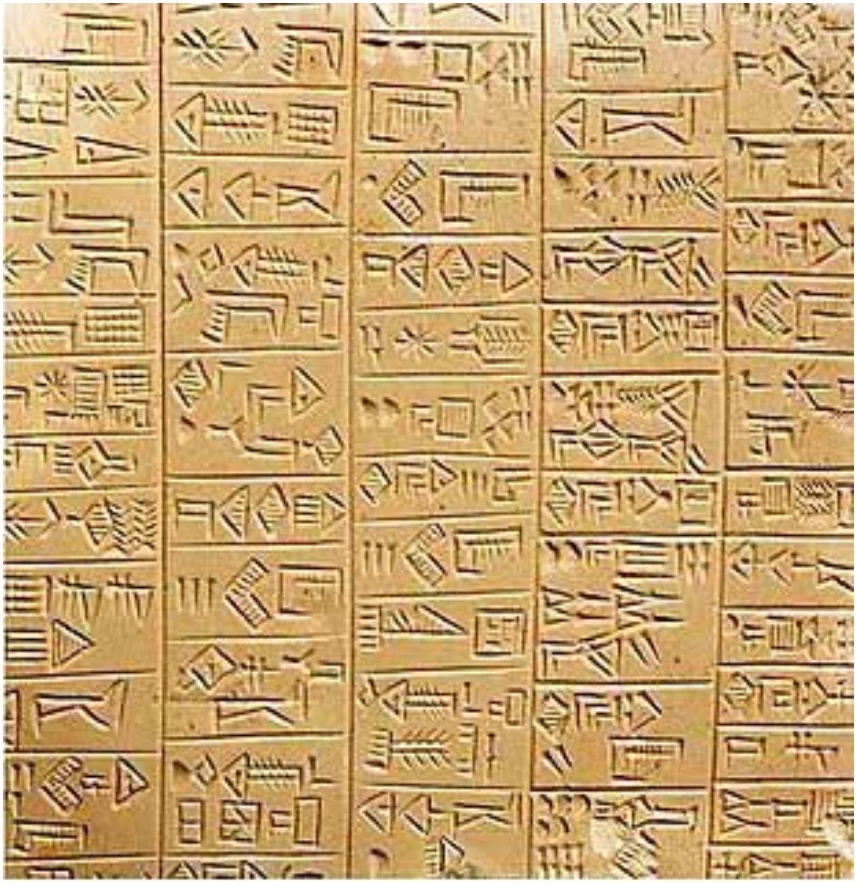

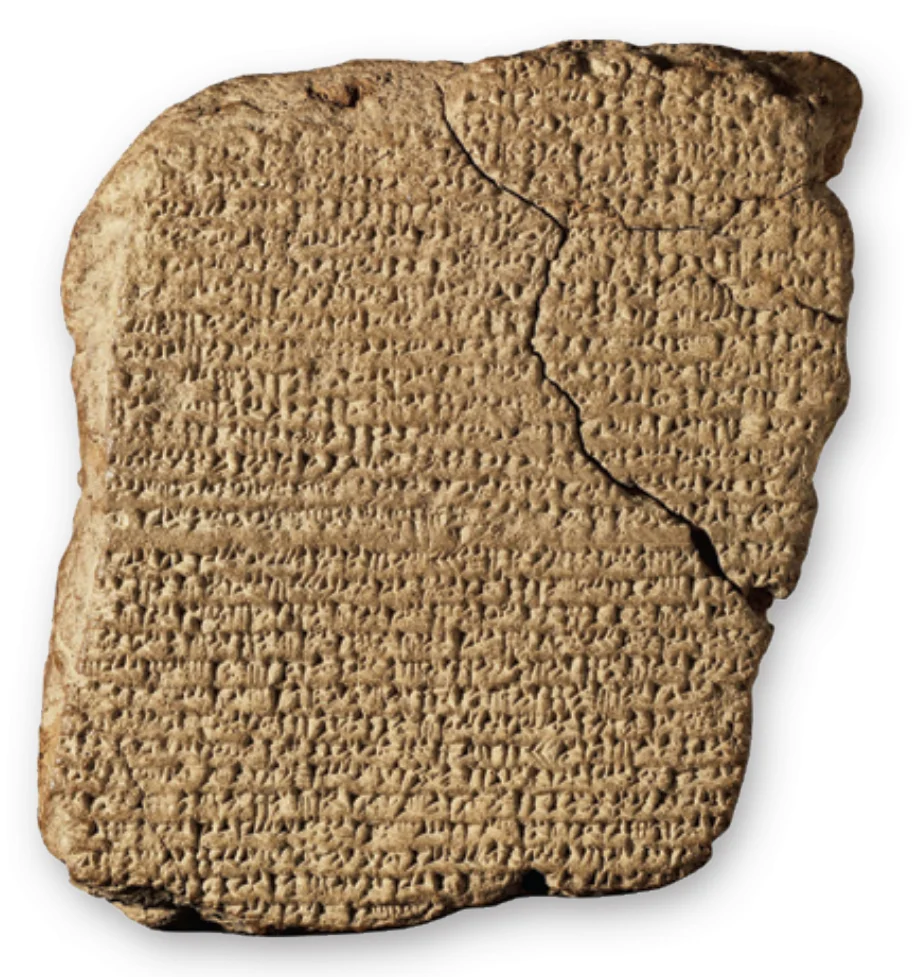

To the west, the fertile plains of Mesopotamia gave rise to the Sumerian civilization around 4500 BCE. The Sumerians are recognized for developing cuneiform script, which stands as one of the earliest known forms of writing. This advancement enabled them to meticulously document administrative records, literary works, and religious texts.

The Sumerians were also notable for establishing some of the earliest city-states, such as Ur and Uruk. These cities became bustling hubs of culture, politics, and commerce, showcasing the Sumerians’ sophisticated urban planning and social organization.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Sumerian culture was their practice of recording celestial omens. Believing these omens to be messages from the gods, priests meticulously documented them on clay tablets and used the information to guide decisions in various aspects of life, from agriculture to warfare.

This practice of celestial documentation was not only religiously significant but also scientifically innovative, influencing subsequent civilizations.

The Sumerians’ contributions laid the groundwork for future civilizations, particularly the Babylonians, who rose to prominence around 1894 BCE. The Babylonians absorbed and expanded upon Sumerian traditions, including the recording of celestial omens, thereby continuing and enriching the legacy of their Sumerian predecessors.

Ancient Egypt

Meanwhile, to the southwest, along the life-giving Nile River, Ancient Egypt was flourishing. Beginning around 3100 BCE with the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under Pharaoh Narmer, this spiritually rich civilization is renowned for its monumental architecture, such as the iconic pyramids of Giza, the Sphinx, and the temples of Karnak and Luxor.

They developed a complex system of writing known as hieroglyphics, which combined logographic and alphabetic elements. This system was used for religious texts, administrative documents, and monumental inscriptions.

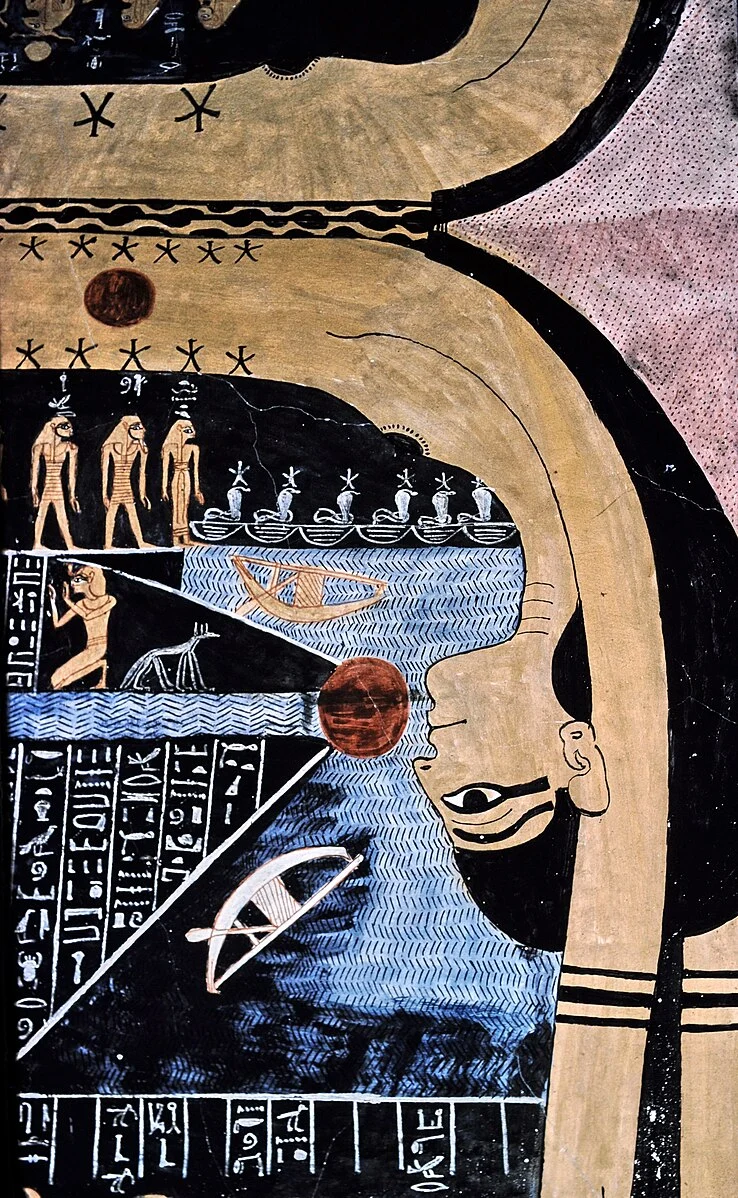

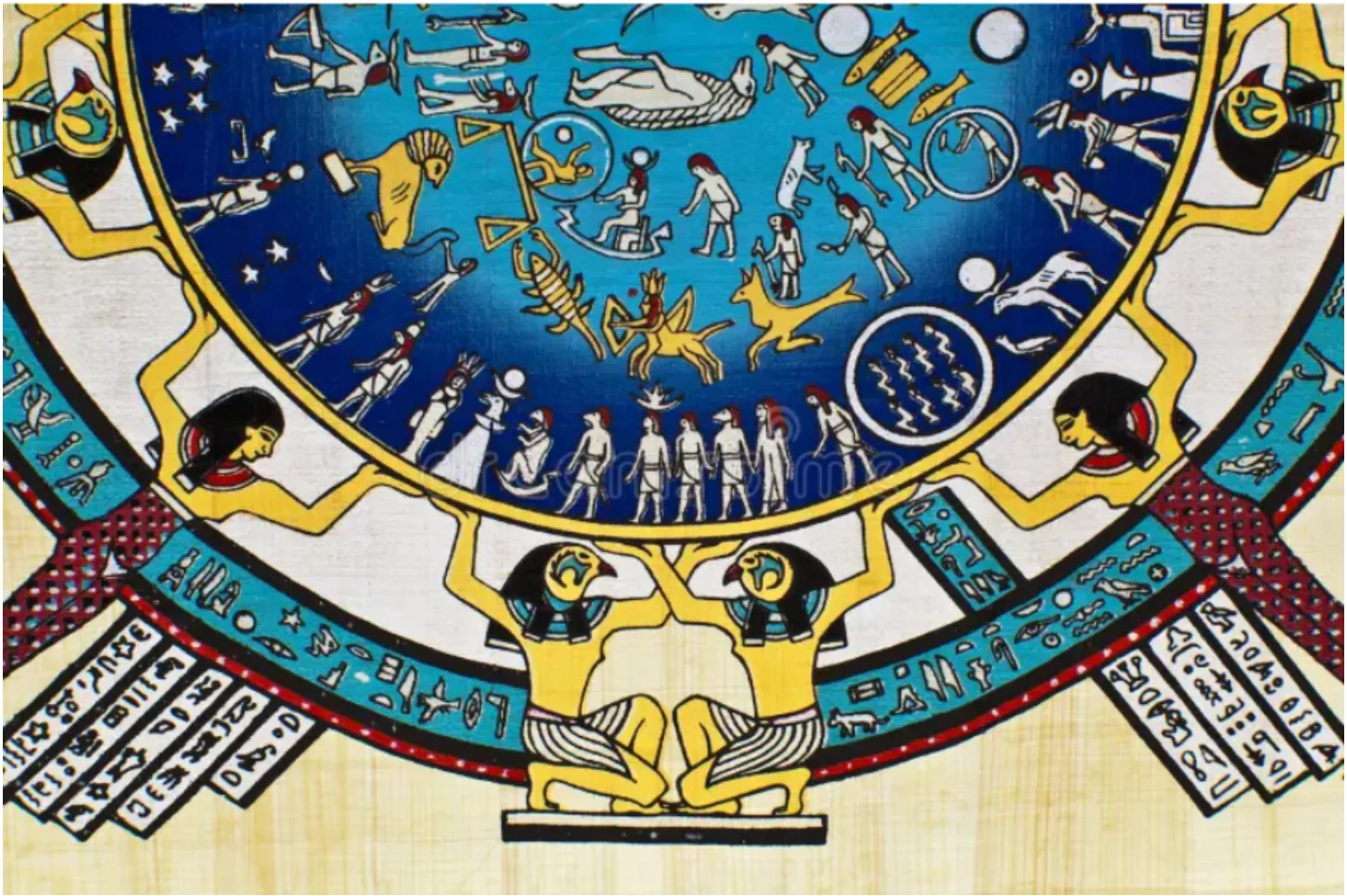

Ancient Egyptian astronomy and astrology were deeply intertwined with their culture, religion, and daily life. The Egyptians are known to have meticulously observed the skies and documented celestial events. The positioning and movement of celestial bodies were often inscribed on tombs and temple walls, reflecting their significance in guiding the deceased through the afterlife.

Ancient Egyptian astronomers were particularly skilled at tracking the cycles of the moon and the stars, which played a crucial role in their calendar system. The heliacal rising of the star Sirius, which coincided with the annual flooding of the Nile, was especially significant, marking the beginning of the agricultural season. This event was celebrated as a time of renewal and fertility, showcasing the Egyptians’ profound connection with the cosmos and its impact on their agricultural practices and spiritual beliefs.

The Ancient Network: Interactions Between Early Civilizations

By 3000 BCE, a thriving trade network connected these civilizations, evidenced by Indus seals found in Mesopotamia and vice versa. Goods such as cotton textiles, beads and pottery were exchanged for silver, lapis lazuli, and other valuable commodities.

The thriving trade network that emerged was not merely a conduit for goods; it was also a vital channel for the exchange of knowledge, culture, and technology. As merchants and travellers moved along these routes, they carried with them new ideas and innovations, which significantly influenced the development of each civilization. The interactions among these civilizations also led to shared religious and mythological themes. Agricultural practices were another area of significant exchange. Techniques for irrigation and crop rotation spread across these regions, enhancing food production and supporting growing populations. Artistic styles and craftsmanship techniques also traversed these trade networks. The intricate beadwork and pottery of the Indus Valley found admirers in Mesopotamia, while Mesopotamian cylinder seals, with their distinctive engraved designs, influenced artistic expression in neighbouring regions. The movement of people and goods facilitated linguistic exchanges, leading to the development of trade languages and the borrowing of scriptural elements. While each civilization maintained its unique language, the necessity of communication in trade encouraged the adoption of a shared vocabulary and scriptural elements, ultimately enriching the linguistic landscape of the ancient world.

In summary, the interactions between these ancient cradles of civilization were multifaceted, fostering a dynamic exchange of goods, ideas, and innovations. This interconnectedness not only enhanced the prosperity of each society but also laid the groundwork for the cultural and technological advancements that followed, shaping the course of human history.

Ancient Greece

As the pages of history turn, our journey takes us to a time of remarkable conquests and cultural exchanges that defined subsequent periods. Having already explored the three ancient cradles of civilization—Indus Valley, Ancient Egypt, and Mesopotamia—we now find ourselves in the heart of the Greek period.

Our tale begins around the 8th century BCE, when the seeds of Greek civilization were first sown. Over the ensuing centuries, this civilization blossomed, reaching its apex during the Classical period of the 5th and 4th centuries BCE. The conquests of Alexander the Great, who reigned from 336 to 323 BCE, were particularly pivotal.

His audacious campaigns stretched from the lands of Greece to the fringes of India, forging an era of cultural amalgamation known as the Hellenistic period.

Alexander’s military expeditions led to the conquest of Babylon, Persia, Egypt, and many other regions, eventually reaching the threshold of India. This period saw the melding of Greek culture with those of the Babylonians, Persians, Egyptians, and many others, fostering advancements in science, art, and philosophy.

However, it is important to recognize that these conquests came at a tremendous human cost. Greek sources often portray Alexander as a great hero and a liberator; however other perspectives cast a more accurate and critical light on his legacy. For instance, Zoroastrian texts, particularly the Arda Viraf, refer to Alexander as “the accursed Alexander” or “Alexander the Destroyer” (Gujastak). These texts accuse him of devastating the Zoroastrian religion and burning sacred texts, highlighting a more violent and destructive side to his conquests. One of the most profound areas of influence of the Hellenistic period was in the realm of astronomy and astrology.

The Greeks, inheriting knowledge from the Babylonians, Egyptians, and other cultures, absorbed these practices, integrating them into their own systems of thought. It was during this era, in the 2nd century CE, that Claudius Ptolemy entered the scene.

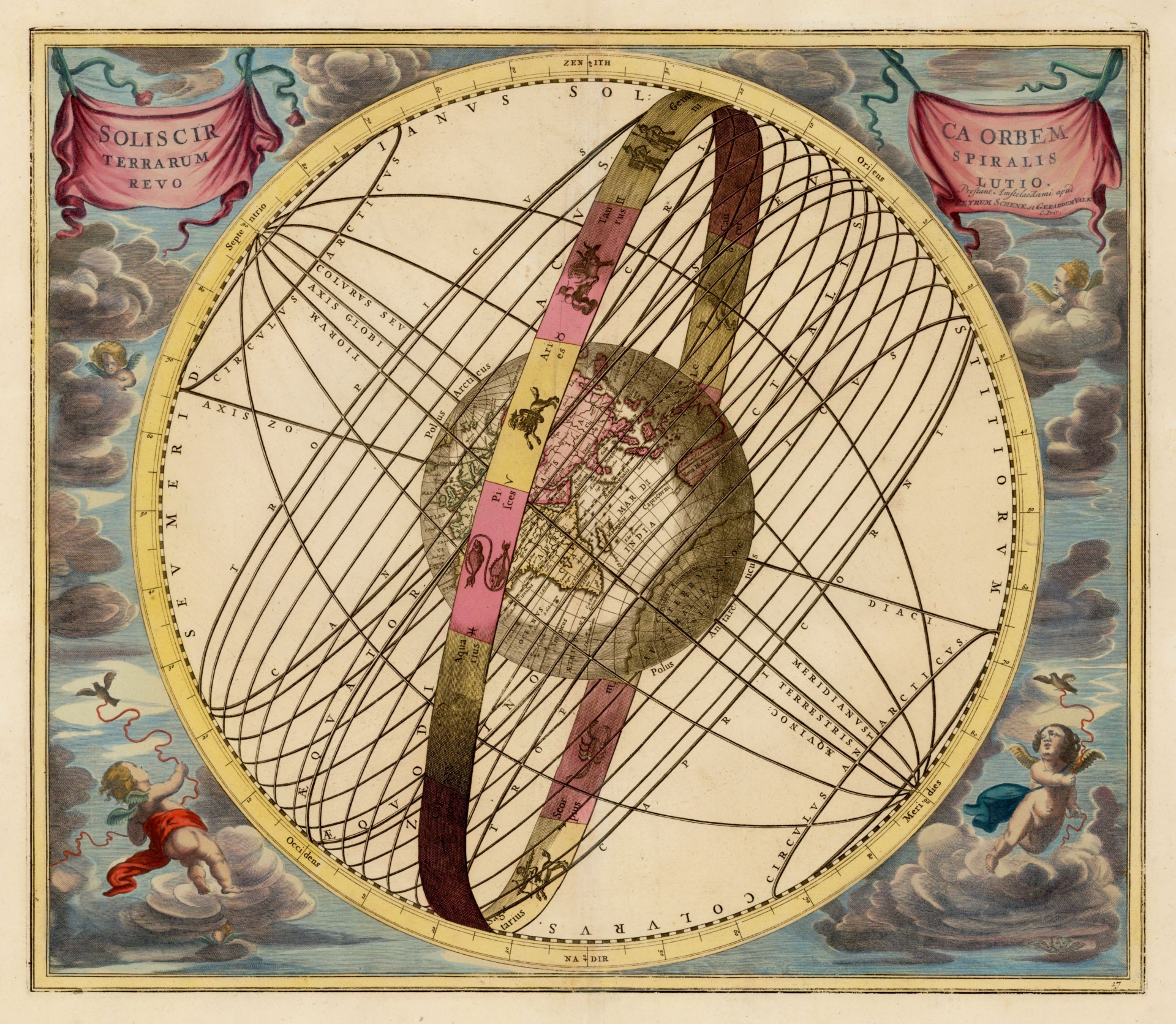

Ptolemy, a Greco-Egyptian scholar, was extremely influential in the fields of astronomy and astrology. His work, particularly the Almagest, synthesized centuries of earlier astronomical knowledge into a comprehensive treatise that would influence both Islamic and European astronomers for centuries.

The blending of these diverse cultural influences laid the groundwork for what would later give rise to Hellenistic astrology, which heavily influenced the birth of modern Western astrology.

Astrology Across Cultures

From the bustling markets of ancient China to the sacred temples of Egypt, and beyond to the mystical lands of the Maya, people gazed at the stars, seeking guidance and understanding. Despite the vast distances and unique traditions, a shared belief in the celestial influence on earthly life united them all, illuminating the rich and varied practice of astrology across the world.

Among the various forms of astrology practised worldwide, Vedic astrology, also known as Jyotish or the study of light, stands out as one of the oldest known systems. Dating back over 5,000 years and rooted in ancient India, Vedic astrology is renowned for its astronomical accuracy.

It uses the real positions of the stars within the sidereal zodiac for its calculations and predictions. This sidereal zodiac divides the sky into 12 rashis or zodiac signs and 27 nakshatras, or lunar mansions, each associated with specific deities, mythologies and characteristics. These nakshatras are star clusters that form a crucial part of the Vedic astrological system.

This intricate framework allows for detailed and profound astrological interpretations, making Vedic astrology a deeply insightful and precise practice.

As we journey from the Indian subcontinent to the fertile lands along the Nile, we find Egyptian priests meticulously observing the stars. The rise of Sirius heralded the annual flooding of the river, a life-sustaining event. The Egyptians categorized the sky into decans—36-star groups that rose consecutively on the horizon in ten-day intervals, thereby marking the hours of the night and enabling them to measure time. These decans were thought to be the manifestations of various deities, influencing fate and destiny. Egyptian astrology, though less commonly discussed today, assigns each person to one of twelve deities based on their birthdate, with each deity believed to influence an individual’s characteristics and destiny.

Moving westward, Western astrology as we know it today is woven from various ancient traditions. During the Hellenistic period, Greek scholars, particularly Claudius Ptolemy, synthesized Babylonian, Egyptian, and other influences.

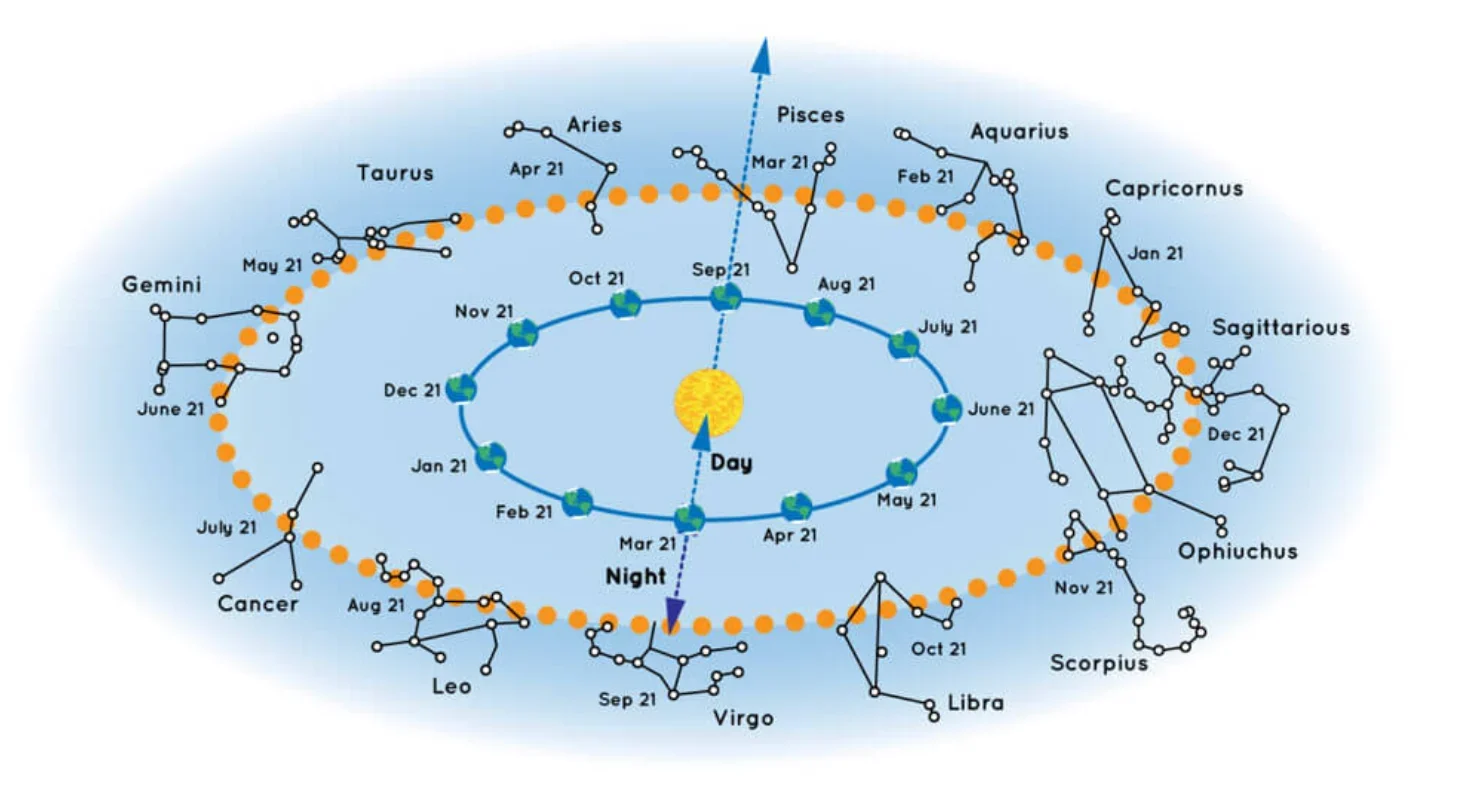

Western astrology uses the tropical zodiac, which is based on the seasons, specifically the equinoxes and solstices.

At one point in the past, it coincided with the actual position of the constellations. However, it now serves more as a symbolic framework for the division of time and space rather than an accurate representation of the planets’ actual positions.

In the Americas, Mayan astrology, rooted in the ancient Mayan civilization, uses a 260-day calendar called the Tzolk’in and involves twenty day-signs and thirteen numbers. Across the waters in Europe, Celtic astrology, another variant, is based on the lunar calendar and the Ogham alphabet, attributing different trees to various periods of the year.

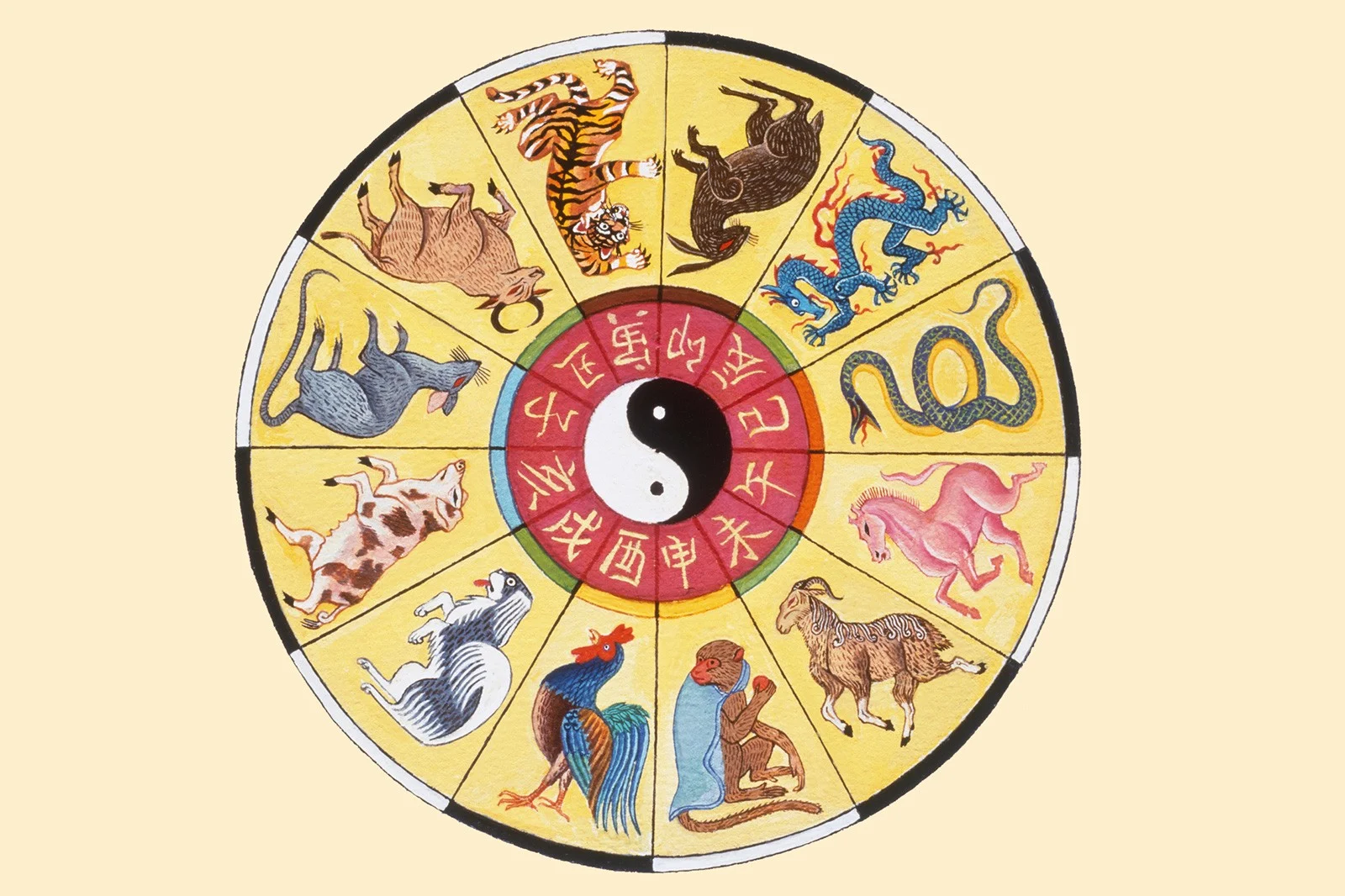

Our journey continues to the Far East, where Chinese astrology follows a lunar calendar and uses a 12-year cycle where each year is associated with one of twelve animals, such as the Rat, Ox, and Tiger.

The world of astrology is vast, with each culture contributing its wisdom and interpretative frameworks to the study of celestial influences on human life.

While several types of astrology exist, only Vedic and Western tropical astrology utilize the movements of planets and zodiac signs. Other astrological systems, such as Chinese, Egyptian, Mayan, and Celtic, diverge significantly from both Vedic and Western astrology, focusing on different celestial or earthly phenomena.

Vedic astrology, with its deep historical roots and continued emphasis on precise astronomical data, stands out for its use of the actual positions of the stars. This alignment embodies the principle of “as above, so below,” making it the only form of astrology that is astronomically accurate. This unique characteristic ensures that its predictions are grounded in real celestial movements, reflecting a cosmic harmony that provides a level of precision unmatched by other astrological systems.

Eastern and Western Philosophy

To understand the difference and polarization between Eastern Vedic Sidereal astrology and Western Tropical astrology, it is essential to delve into the fundamental distinctions in Eastern and Western philosophy, as these cultural underpinnings significantly influence the respective astrological traditions and the use of the two distinct zodiacs.

Eastern Philosophy

Eastern philosophy, woven from the diverse thoughts and traditions of regions such as India, East Asia, and Southeast Asia, offers profound insights into life, ethics, and existence. It illuminates the path to harmony, balance, and the natural order, often emphasizing the interconnectedness of all life and the dissolution of the self into a larger whole.

Confucianism, originating from the teachings of the venerable Chinese philosopher Confucius (Kong Fuzi), is a system of ethical and philosophical thought that has profoundly shaped East Asian cultures. At its heart lies the concept of “Ren,” a radiant principle often translated as “benevolence” or “humaneness.” It emphasizes the importance of compassion, empathy, and loving-kindness in human interactions. Confucius envisioned Ren as the bedrock of a harmonious society, where individuals act with moral integrity and prioritize the well-being of others.

Buddhism introduces the profound and mystical concept of anatta, which translates to non-self. This idea suggests that the self, as we commonly perceive it, is but an illusion. According to Buddhist teachings, the belief in a permanent, unchanging self is a source of suffering and ignorance. By grasping and embracing the concept of anatta, individuals can glimpse the interconnectedness of all things and the ever-changing nature of existence. This revelation is pivotal on the path to enlightenment, encouraging the relinquishment of ego and personal desires that often lead to attachment and suffering. To reach enlightenment, one must transcend the illusion of the self, engaging in meticulous self-examination and meditation practices designed to dismantle the ego. Through this, practitioners may experience a profound sense of inner peace and liberation from the cycle of rebirth and suffering.

Taoism, an ancient Chinese spiritual and philosophical tradition, beckons individuals to live in harmony with the Tao. The Tao, often translated as “The Way,” embodies the fundamental nature of the universe and the underlying order of all things. Taoist teachings emphasize the importance of aligning oneself with this natural order to achieve a state of flow and equilibrium. In doing so, individuals can lead a more balanced and fulfilling life, free from unnecessary stress and conflict. Living in accordance with the Tao involves embracing simplicity, humility, and spontaneity, allowing life to unfurl naturally. This approach fosters a sense of inner peace and contentment, as one learns to navigate the ebb and flow of existence with grace and ease. In essence, Taoism offers a magical path to harmony and well-being, attuned to the rhythms of the natural world.

Sanātana Dharma, meaning “eternal dharma” or “eternal order,” is the ancient name for Hinduism. It transcends the conventional notion of religion by offering a profound understanding of the nature of the universe and the interconnectedness of all beings. This timeless wisdom invites exploration of the nature of existence, fostering a sense of responsibility and unity that is relevant to all humanity, regardless of cultural or spiritual backgrounds. Much like astrology, where the influence of planets and celestial bodies is impartial to one’s beliefs or cultural affiliations, their effects permeate the fabric of existence, shaping experiences and events in ways that transcend individual affiliations.

Just as gravity exerts its pull without regard for one’s background or whether one acknowledges its existence, the energies of the cosmos interact with all beings, inviting a shared exploration of our place in the universe. This universality serves as a reminder that we are all part of a larger cosmic rhythm, urging us to recognize our commonality in the face of diverse perspectives. At its core is the concept of Dharma, which refers to the moral order of the universe and an individual’s duty to uphold this cosmic order.

Dharma is not a rigid doctrine but a dynamic, living principle that adapts to the context of one’s life, emphasizing internal integrity, ethical behaviour, and a strong moral compass. The concept of Dharma encourages individuals to look inward and cultivate virtues such as truthfulness, patience, humility, and self-discipline. It is an internal compass that guides one’s actions in alignment with the greater good, transcending selfish desires and ambitions.

In essence, Dharma is about maintaining a balance between one’s own needs and the needs of the collective, between personal desires and universal laws. It is about making choices that are ethical and just, even when those choices are difficult. Through the practice of Dharma, individuals can achieve inner peace and fulfilment.

Another fundamental aspect of Hinduism is the belief in Karma, a universal law of cause and effect that posits every action has consequences, manifesting either in this life or future incarnations. This belief supports a cyclical view of time and existence, where the soul evolves and progresses through various life forms based on accumulated karma. The ultimate goal in Hinduism is Moksha (Nirvana), or liberation from the cycle of death and rebirth known as Samsara, achieved through spiritual knowledge, righteous living, and devotion. Hinduism places a significant emphasis on the spiritual and metaphysical realms, advocating for a deeper, inner realization of the self’s unity with the divine.

In the realm of spiritual versus material pursuits, Eastern philosophy values the spiritual over the material. The teachings of Hinduism and Buddhism emphasize inner growth, mindfulness, and the pursuit of enlightenment.

The focus is on conquering the self, achieving inner peace, and understanding one’s place in the universe. Material possessions and external achievements are seen as transient and secondary to spiritual fulfilment. Eastern philosophy emphasizes the soul’s journey, karmic consequences, reincarnation, and liberation, reflecting a worldview where time is cyclical and each life is a step in a broader cosmic process.

Western Philosophy

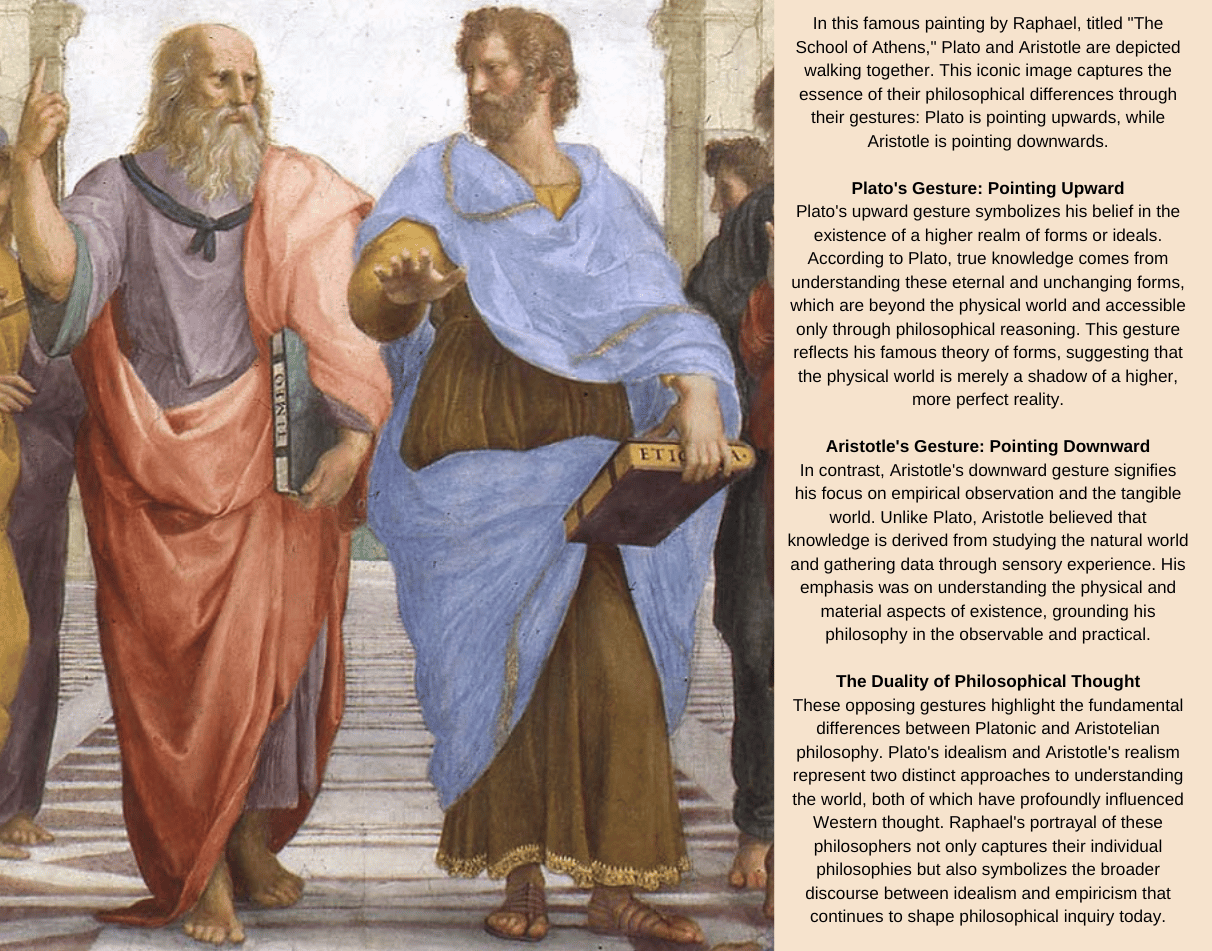

Western philosophy, deeply influenced by ancient Greek thinkers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, has long emphasized analytical and individualistic approaches. With its roots stretching back to ancient Greece, it has been a cornerstone in the development of intellectual thought.

From the Socratic method of questioning to Aristotle’s logical rigor, Western philosophy has provided frameworks for understanding the world and our place within it. It has fostered critical thinking, political theory, and metaphysics, influencing not just academic circles but also everyday life, governance, and science. Philosophers such as Descartes, Kant, and Nietzsche have shaped discourses around reason, existence, morality, and power, making significant contributions to human knowledge. Western traditions prioritize the material and empirical world, emphasizing empirical evidence and scientific inquiry as the basis for understanding existence.

Central to many Western philosophies is the emphasis on personal freedom and autonomy, reflecting an individualistic ethos. This perspective often views reality through a linear lens, focusing on a single lifetime culminating in a final judgment or eternal fate. This individualistic ethos is closely tied to the Western focus on achievements and material success. In a society that prizes personal autonomy and self-determination, success is frequently measured by tangible accomplishments. The pursuit of higher education, career advancements, and financial stability are often seen as benchmarks of a successful life. This emphasis can drive innovation and economic growth, but it also places immense pressure on individuals to constantly strive for more.

Western philosophy has a rich and diverse history, but one recurring theme is the emphasis on the self, which has both illuminated and constrained our understanding of the world. Philosophers such as Descartes, with his famous declaration “Cogito, ergo sum” (I think, therefore I am), placed the self at the heart of philosophical inquiry. This introspective focus has contributed significantly to the development of individualism and personal identity in Western thought.

However, this emphasis on the self can also be seen as a limitation, as it can foster a narrow view of existence that overlooks the interconnectedness of all things. This anthropocentric perspective, much like the once-prevailing geocentric belief that the Earth was the centre of the universe, has often led to a skewed view of reality.

The geocentric model of the universe, championed by Ptolemy and later challenged by Copernicus, is a metaphor for the broader human tendency to view ourselves as the centre of all things. This perspective can lead to an inflated sense of importance and a disregard for the broader context within which we exist. Philosophies that prioritize the self may inadvertently encourage a form of solipsism, where the external world is seen as secondary to individual perception and experience.

The dichotomy of “conquer the world vs. conquer the self” further highlights these philosophical differences.

Western philosophy often encourages the conquest of the external world, reflected in the drive for exploration, technological innovation, and the manipulation of the environment to better human conditions. On the other hand, Eastern philosophies prioritize self-conquest, advocating for self-discipline, internal harmony, and personal enlightenment, such as through the practice of meditation aimed at mastering the mind and emotions.

One of the major critiques of Western philosophy is its historical Eurocentrism, often marginalizing non-Western perspectives and contributions. The dominance of Western thought has also been accused of perpetuating colonialist attitudes, where the “Western” way is seen as superior or more advanced.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s “Philosophy of History” dismissed African societies as static and unimportant to the course of world history. “Africa… is no historical part of the World; it has no movement or development to exhibit.” This dehumanizing perspective was used to justify the subjugation and exploitation of African peoples by European colonizers.

In “Idea for a Universal History with a Cosmopolitan Purpose,” Immanuel Kant suggested that European civilization represented a higher stage of human development. This Eurocentric view implied that other cultures were less advanced and thus needed to be “civilized,” which was a common justification for colonialism.

In “Leviathan,” Thomas Hobbes described indigenous peoples in the Americas as living in a “state of nature” characterized by chaos and lack of governance. “The savage people in many places of America… have no government at all, and live at this day in that brutish manner, as I said before.” This portrayal was employed to rationalize colonial rule as a means of bringing order and civilization.

These examples illustrate how Western philosophical thought has been used historically to support and legitimize colonialism. They reflect a broader trend of Eurocentrism and ethnocentrism that viewed non-European cultures as inferior and in need of Western intervention.

Imagine Earth as a grand school, where individuals, nations and cultures are students navigating the complex syllabus of life. Just like any schoolyard, you’ll find a spectrum of behaviours—the kind and the supportive, but also, regrettably, the bullies. These playground bullies, much like certain Western powers during the era of colonization, have a habit of stealing your lunch. They didn’t just take sandwiches and apples; they drained wealth and resources, leaving behind an economic void. These bullies react defensively when they perceive a challenge to their own status or achievements. Negative press and derogatory stereotypes become their weapons of choice, aiming to belittle and undermine.

Take, for instance, South Korea’s rise in technology was initially dismissed as mere imitation and Japan’s economic boom in the 1980s was met with fear-mongering and caricatures. Similarly, when India achieved its Mars mission, Mangalyaan, the Western media opted for mockery instead of celebration, using condescending cartoons to diminish this incredible feat. More recently, as India became the first country to land on the south pole of the moon, a remarkable achievement in space exploration, a British news reporter chose to make derogatory remarks. Such pettiness reminds us of the persistent biases that linger within global narratives.

A more balanced and comprehensive understanding of existence would recognize the importance of the self while also acknowledging our place within a larger, interdependent cosmos. Ultimately, a shift away from an overemphasis on the self could lead to a more inclusive and harmonious worldview, fostering greater empathy and cooperation among individuals and communities.

The Essence of Civilization

What does it truly mean to be “civilized”? Is it merely the adoption of a sophisticated facade, adorned in tailored suits and residing in opulent surroundings, while harbouring no qualms about exploiting others to preserve one’s own comfort? Or is it found in those who choose a path of humility, living in harmony with the natural world and embracing a life of simplicity and respect?

In the story of our human existence, civilization should not be measured by material wealth or technological prowess but by the depth of empathy, the strength of community, and the commitment to living in balance with the world around us.

A well-suited devil remains a devil, regardless of the elegance of their attire. True civilization is reflected in the ability to coexist peacefully, with a deep understanding of our interconnectedness and a profound respect for all forms of life. The civilized are those who uplift others, not those who trample over them in their pursuit of power.

Alexander the Great Meets an Indian Sage, Kalanos

The encounter between Alexander III of Macedon and the Indian sage Kalanos is a fascinating tale that highlights the clash of different cultures and philosophies. Alexander, one of history’s most renowned military leaders, was significantly influenced by the teachings of the Greek philosopher Aristotle.

Aristotle, a towering figure in Western philosophy and a student of Plato, was hired by Alexander’s father, King Philip II of Macedon, to tutor the young prince at around 13 years old. This mentorship profoundly shaped Alexander’s intellectual and cultural outlook.

By the age of 16, Alexander began his illustrious military career, demonstrating his burgeoning leadership skills by quelling a rebellion in Thrace and founding the city of Alexandropolis. His ambition led him to orchestrate a series of conquests, including the powerful Persian Empire, Babylon, Egypt, and parts of Asia Minor, Syria, and Phoenicia. His unrelenting drive pushed him further east through Mesopotamia, Bactria, and eventually into the thresholds of the Indian subcontinent around 327-325 BCE.

Interestingly, around the age of 27, Alexander reached India just in time for his Saturn Return, a significant astrological event that symbolizes a period of intense transformation, self-reflection, and karmic reckoning.

During his campaign in India, Alexander’s quest for knowledge led him to seek out local sages and philosophers. According to historical accounts, particularly those of Plutarch, Alexander encountered the sage Kalanos, who lived a life of asceticism and meditation. Intrigued, Alexander approached him, hoping to engage in a philosophical dialogue.

The sage, unfazed by the presence of the great conqueror, continued his meditation. When Alexander asked him what he was doing, Kalanos replied that he was contemplating the nature of the universe and his place within it. He then turned the question back to Alexander, asking why he was undertaking his conquests. Alexander responded that he sought to conquer the world and achieve everlasting fame.

Kalanos’ response was thought-provoking and filled with profound wisdom. He remarked that Alexander was not a conqueror but a prisoner to his desires. The sage, having conquered the desire to conquer, emphasized that true freedom and wisdom come from within, not through external conquests. This encounter is often cited as a poignant moment where Western aspirations of power and conquest intersected with Eastern philosophy of inner peace and enlightenment.

Interestingly, Plato had philosophized about self-conquest, stating, “The first and best victory is to conquer self. To be conquered by self is, of all things, the most shameful and vile.” This means that mastering one’s own desires and impulses is the highest form of victory, while succumbing to them is the lowest. The irony here is palpable; Alexander, despite his philosophical education, failed to embody this wisdom. Aristotle himself was a student of Plato, highlighting that it is not enough to philosophize; one must walk the talk and embody these teachings in their actions.

Aristotle had asked Alexander to seek out and bring back a wise Indian philosopher to meet him, among other desires like collecting rare plants and soil samples. Alexander attempted to take Kalanos with him back to Persia, driven by a desire for the sage’s wisdom and spiritual abilities. Alexander believed that Kalanos could provide valuable insights and divine guidance for his future endeavours.

Kalanos was reluctant to leave his homeland and way of life. However, Alexander, known for his determination and forceful methods, managed to take Kalanos with him. During their journey, Kalanos, 73 years old at this time, became increasingly weak and sick. Before his death, Kalanos chose a dramatic and poignant way to depart from the world. He self-immolated, a practice of setting oneself on fire, not uncommon among Indian and Buddhist monks/ascetics who sought liberation from the cycle of life and death.

Kalanos had been a teacher to Alexander and many Greek soldiers. Before his death, Kalanos is said to have bid farewell to the soldiers but not to Alexander. Instead, he made a prediction to Alexander: he told the conqueror that they would meet again in Babylon.

True to his words, Alexander returned to Babylon a year later, where he mysteriously died at the age of 32 in 323 BCE. This eerie prediction added a layer of mysticism to the already complex and intriguing tale of Alexander’s encounters with Indian sages. Alexander’s hubris, excessive pride and ambition, ultimately led him to overextend his reach, and his attempt to conquer India was his last campaign. His legacy is remembered not only for his conquests but also for the cultural diffusion and the Hellenistic influence that spread across the regions he conquered, shaping the course of history for centuries to come.

Alexander’s approach to seeking knowledge through force and aggression contrasted starkly with the teachings of Hinduism. This sentiment echoed the Eastern philosophy that wisdom is to be obtained by true seekers, and not through aggression, arrogance, or force.

As Yoda, the iconic Jedi Master from Star Wars, wisely said:

“But beware of the dark side. Anger, fear, aggression; the dark side of the Force are they. Easily they flow, quick to join you in a fight. If once you start down the dark path, forever will it dominate your destiny, consume you it will.”

Luke Skywalker: Is the dark side stronger?

Yoda: No, no, no. Quicker, easier, more seductive.

Luke Skywalker: But how am I to know the good side from the bad?

Yoda: You will know. When you are calm, at peace, passive.

A Jedi uses the Force for knowledge and defence, never for attack.

The Two Systems and The Two Clocks

Astrology is broadly categorized into two primary systems: Eastern Vedic Sidereal and Western Tropical. Both systems share fundamental elements such as the use of the zodiac signs, twelve houses, and planetary transits, but they diverge significantly in their methodologies and the zodiac systems they utilize.

Vedic Astrology and the Sidereal Zodiac

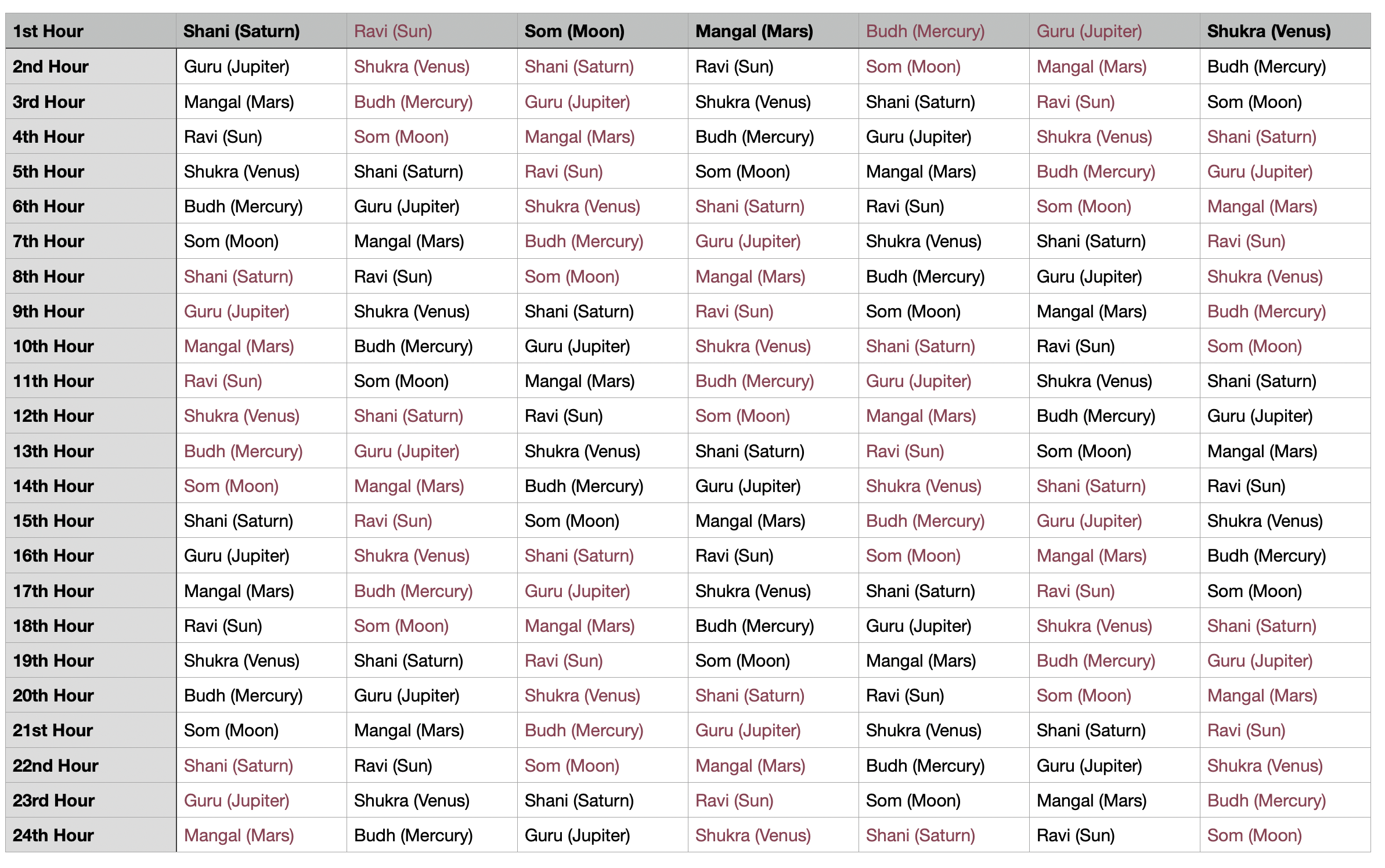

Vedic astrology uses the Sidereal zodiac, which is astronomically accurate and reflects the true positions of the planets in the sky. The Sidereal zodiac accounts for the precession of the equinoxes, which is the gradual shift in Earth’s rotational axis caused by the gravitational pull of the Sun and Moon. This phenomenon leads to a change in the positions of the stars, as observed from Earth, over extended periods of time.

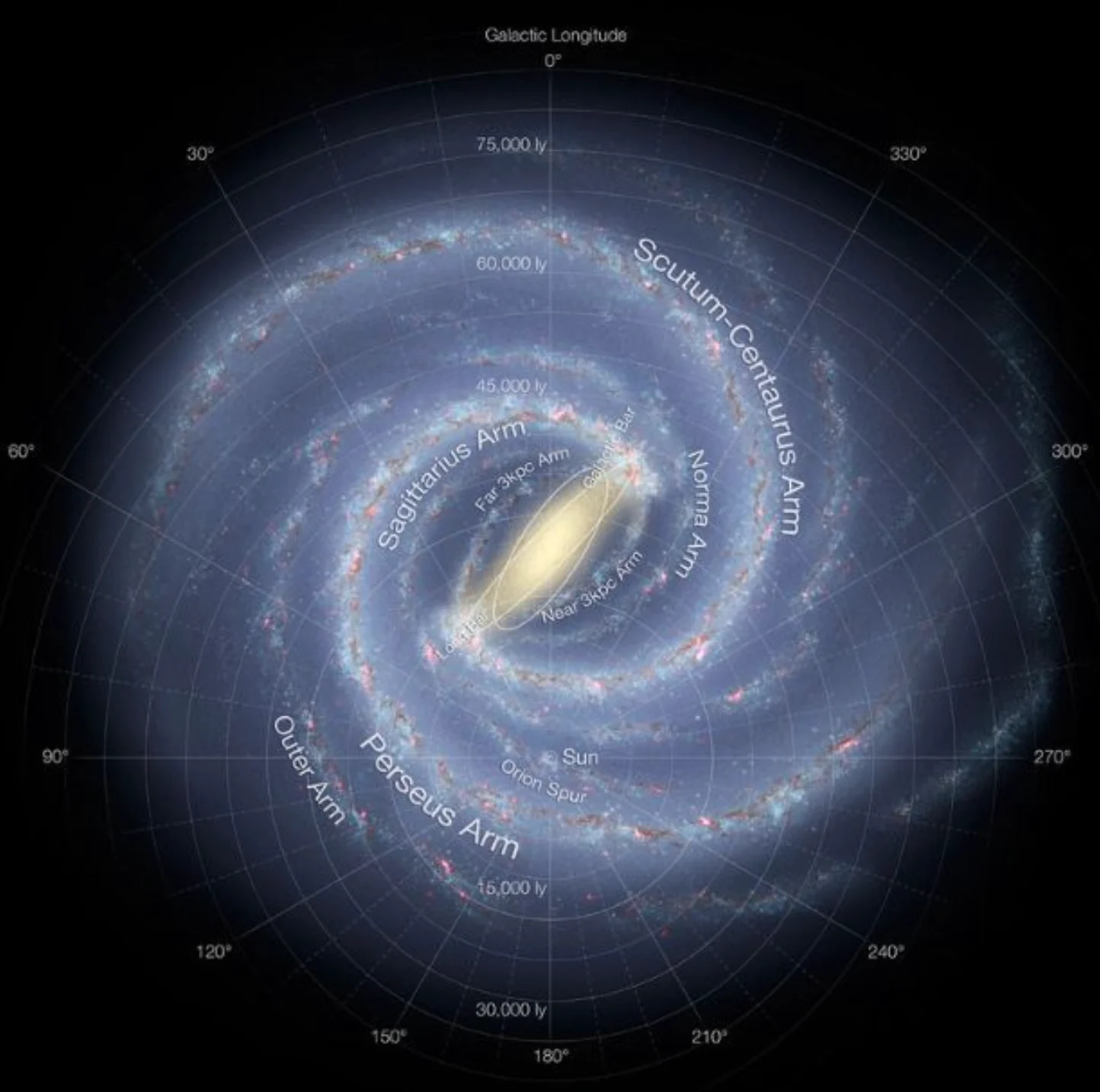

This system maintains the relationship between Earth and the Galactic Center, the core of the Milky Way, ensuring that astrological readings remain connected to our galactic home. As the Earth revolves around the Sun and the Sun revolves around the Galactic Center, the Sidereal zodiac keeps us aligned with the fixed stars and the centre of our galaxy.

Due to this precise alignment, the Sidereal zodiac remains eternally accurate, reflecting the true celestial mechanics. The Sidereal zodiac’s adherence to the actual star positions provides a stable and consistent framework for astrological interpretations. This ensures that the insights and predictions derived from Vedic astrology are deeply rooted in cosmic order, offering a timeless connection to the universe.

Western Astrology and the Tropical Zodiac

In contrast, Western astrology uses the Tropical zodiac, based on the relationship between Earth and the Sun. The Tropical zodiac is oriented around the seasons of the Northern Hemisphere rather than the actual positions of the stars. It assumes that 0 degrees Aries always begins at the vernal equinox, around March 21st. However, this system does not account for the precession of the equinoxes, ignoring the connection to the true positions of the stars, making it astronomically inaccurate. While it once accurately reflected the positions of the stars, over time, due to precession, the positions have shifted by approximately 24 degrees and will continue to drift.

Part II – The Tropical Zodiac and Its Drifting Resonance discusses the gradual shift in the alignment of the tropical zodiac over time. It highlights that any perceived connections or resonances with the tropical zodiac are temporary and are largely due to the current 24-degree difference between the tropical and sidereal zodiacs. As a result, when individuals feel a resonance with a tropical zodiac sign based on their Sun sign, it might actually be due to the positions of planets like Mercury or Venus in the sidereal zodiac, since these planets are always near the Sun. Therefore, what they assume to be their Sun sign might, in fact, be the influence of their Venus sign or Mercury sign.

Part II -The Role of the Tropical Zodiac in Ancient Agriculture also delves into the ancient agricultural roots of the tropical zodiac. It highlights how the tropical zodiac was a reflection of its era—a product of its time—and how its concept is only applicable to specific areas in the Northern Hemisphere, rather than universally. The text challenges the accuracy of interpreting astrological influences on human life through the agricultural lens of an ancient society.

Part II – Discrepancy in the Assessment of Planetary Dignities explores how the tropical zodiac misrepresents planetary dignities by failing to align them with the planets’ actual positions in the sky. Planetary dignities refer to the strengths and weaknesses of planets based on their positions in relation to the zodiac signs. Each planet has certain signs where it is considered strong or weak.

For example, a planet is in its domicile (home) when it resides in the sign it rules, such as the Moon in Cancer or the Sun in Leo. In these positions, the planets express their energies most effectively. Conversely, when a planet is in a sign opposite to its domicile, known as detriment, it struggles to express its qualities. For instance, Mars is in detriment in Libra, where its assertive nature can be subdued by the sign’s indecisiveness.

There are also other dignities, such as exaltation, where a planet feels particularly empowered, like the Sun in Aries, and fall, where it is weakened, such as Saturn in Aries. Understanding these dignities helps astrologers assess how planetary influences manifest in a person’s chart, indicating areas of strength and potential challenges.

This tropical system assigns planetary strengths and meanings based on a fixed framework that does not account for the precession of the equinoxes, causing a significant shift over time. For example, say Venus is transiting tropical Scorpio. Venus is in detriment when transiting through Scorpio, suggesting challenges and discomfort. However, according to the sidereal zodiac, which aligns more accurately with the current astronomical positioning, Venus would actually be in its domicile or home in sidereal Libra during this time, where it enjoys harmony and strength.

This discrepancy highlights a fundamental flaw in the tropical zodiac’s approach, as it overlooks the true celestial coordinates, leading to potentially misleading interpretations of planetary influences.

While employing the tropical zodiac can indeed still provide many accurate predictions based on planetary transits through houses and aspects to planets, its predictions can be seen as “truth mixed with lies” due to incorrect planetary dignities.

The Tropical zodiac operates much like a stopped clock that is correct twice a day; it only aligns with its original celestial coordinates once every precession cycle of approximately 26,000 years. The tropical zodiac, in essence, functions like a timepiece frozen in an era long past. It reflects the positions of the stars as they were roughly 2,000 years ago, during its inception. Therefore, relying on the tropical zodiac for precise astrological readings today is like depending on a stopped clock for accurate timekeeping.

This inaccuracy means that the future of mankind cannot depend on this outdated system. Even if change is not imminent, we must consider future generations and the evolution of astrology. Adopting the correct sidereal zodiac, which aligns with the actual positions of the stars, is essential for ensuring that astrological knowledge remains accurate and continues to be transferred reliably from generation to generation.

Philosophical Underpinnings

The use of these zodiacs reflects the underlying philosophical differences between the two systems. Western Tropical astrology, with its emphasis on the Sun, focuses solely on Earth’s relationship with the Sun through Equinoxes and Solstices, ignoring the connection to the true positions of the stars and the center of our galaxy. Some advocates of the tropical zodiac argue that the distant stars are ‘too far’ to impact human existence, emphasizing our relationship with our local star—the Sun.

The Sun symbolizes the self, ego, and identity, aligning with Western philosophy’s focus on individualism. Ironically, Western Tropical astrology ultimately overlooks the astronomical reality of the Sun’s position, insisting on placing the Sun in Aries at the vernal equinox, when it is actually in the Pisces constellation.

On the other hand, Eastern Vedic Sidereal astrology accounts for our interconnectedness with the cosmos, reflecting Eastern philosophy’s emphasis on harmony, balance, and the dissolution of the self into a larger whole. This perspective aligns with the concept of quantum entanglement, a phenomenon in quantum physics where particles become interconnected in such a way that the state of one particle instantaneously influences the state of another, regardless of the distance between them. Quantum entanglement suggests that everything in the universe is interconnected, mirroring the Eastern philosophical belief in the unity of all life and the importance of understanding our place within the broader cosmic context.

By recognizing the interconnectedness of all things, Eastern Sidereal astrology and philosophy encourage a more holistic and inclusive worldview. This perspective fosters a deeper understanding of the universe, ultimately promoting a sense of harmony and balance that transcends individual ego and material pursuits.

The Two Legacies

Ptolemy’s Controversial Legacy

The Hellenistic Period and Hipparchus’ Contributions

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, the world entered a transformative era known as the Hellenistic period. This era was marked by significant advancements in various fields, including astronomy and astrology. One of the most prominent astronomically important events during this period was the work of Hipparchus of Nicaea. Hipparchus, who lived around 190-120 BCE, is often regarded as one of the greatest astronomers of antiquity in the western world. Hipparchus made significant contributions to the understanding of the cosmos and is credited with the discovery of the precession of the equinoxes.

(While Hipparchus’ realization of this phenomenon was groundbreaking, it’s important to acknowledge that Indian astrologers and astronomers had been aware of precession and had been using the sidereal zodiac, which accounts for precession, for thousands of years prior to his time. This highlights the rich and diverse history of astronomical knowledge across different cultures.)

Claudius Ptolemy’s Synthesis and Contributions

Amid this cultural fusion emerged Claudius Ptolemy, a Greco-Egyptian scholar who played a pivotal role in synthesizing knowledge from various ancient civilizations, including the Babylonians, Egyptians, and other traditions. Ptolemy, who lived during the 2nd century CE, made significant contributions to astronomy, geography, and astrology, with his most famous work being the “Almagest,” a comprehensive treatise on the geocentric model of the universe.

In another influential work, the “Tetrabiblos,” Ptolemy laid the foundation for Western tropical astrology, detailing the astrological significance of celestial bodies and their positions relative to Earth. Ptolemy’s work was built upon the foundations laid by his predecessors, including Hipparchus, and his influence persisted well into the medieval period, shaping the course of scientific thought for centuries.

Controversies Surrounding Ptolemy’s Work

Despite the importance of precession, discovered by his predecessor Hipparchus, Ptolemy chose to ignore it in his works, likely perceiving it as a threat to his geocentric theories. By disregarding precession, Ptolemy avoided challenging the prevailing paradigms of his time, which heavily favoured a geocentric model of the universe with Earth at its center. This adherence to orthodoxy could be seen as a strategic move to maintain his esteemed position within the scientific community and avoid controversy.

Moreover, the phenomenon of precession changes the position of the equinoxes by only about 1 degree every 72 years. Ptolemy might have considered this shift irrelevant for his lifetime and immediate future, adopting a ‘not my problem’ attitude. This glaring omission raises questions about the integrity and thoroughness of Ptolemy’s scientific approach. It suggests that his commitment to preserving the geocentric model may have overshadowed his dedication to empirical evidence and objective inquiry.

Allegations of Fraudulent Data and Influence

It has been widely debated among historians and scholars that Ptolemy used fraudulent data in his astronomical observations and calculations. Critics argue that Ptolemy’s data often appears to be too precise and conveniently aligns with his theoretical models, suggesting that he may have manipulated or selectively reported observations to fit his preconceived notions. For example, discrepancies have been found when comparing Ptolemy’s star catalog to the positions of stars recorded by other astronomers of his time, such as Hipparchus. This has led to accusations that Ptolemy might have borrowed and adjusted earlier observations to bolster the credibility of his geocentric model. Moreover, some scholars believe that Ptolemy’s work was not entirely original. They assert that he heavily relied on the findings and theories of his predecessors, including those of Babylonian and Greek astronomers, and presented them as his own. This practice, coupled with the potential manipulation of data, raises questions about the authenticity and ethical standards of his scientific contributions.

Legacy and Modern Reassessment

Despite these controversies, Ptolemy’s works, particularly the “Almagest,” remained influential for centuries, shaping the course of astronomical and astrological thought throughout the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance.

In modern times, the scientific community has sought to correct and build upon Ptolemy’s work. The understanding of the precession of the equinoxes, initially overlooked by Ptolemy, was later refined by astronomers and eventually incorporated into the heliocentric models (which describe the Sun as the center of the universe) proposed by Copernicus and Galileo.

This discrepancy between the western tropical zodiac championed by Ptolemy and the true position of the constellations has led many in the Western scientific community to dismiss astrology as pseudoscience or “mumbo-jumbo.” In 2016, NASA published an article on their educational site for children, Space Place, which caused a quite a stir among astrology enthusiasts. Most were not even aware that their tropical zodiac placements didn’t align with the constellations.

“Astronomy is the scientific study of everything in outer space,” wrote NASA. “Astrology is something else. It’s not science.”

The Western scientific community often dismisses astrology as invalid without thorough testing, relying instead on preconceived notions and biases. This dismissal largely stems from the astronomical inaccuracy attributed to Western astrology’s use of the tropical zodiac rather than the sidereal zodiac. However, if scientists were to observe their astrological transits, even for a short period, they will recognize the effects and manifestations of these celestial patterns in their daily lives, potentially challenging their initial skepticism and demonstrating the accuracy and energy that astrological phenomena can impart. By documenting personal experiences and correlating them with astrological transits, scientists might uncover patterns that align with astrological predictions, prompting a reevaluation of the discipline’s validity. This empirical approach could bridge the gap between astrology and science, fostering a more nuanced understanding that transcends traditional biases.

Bridging the Gap Between Science and Astrology

There are forces in the universe that cannot be fully measured or explained but they are undeniable. Dark matter, Quantum Entanglement, and other complex scientific concepts were once beyond the scope of human understanding but are now integral to our comprehension of the cosmos. Dismissing astrology outright without thorough investigation is indeed a missed opportunity to uncover hidden truths about the universe. By keeping an open mind and applying rigorous scientific methods, we can bridge the gap between traditional scientific paradigms and alternative perspectives, ultimately enriching our collective knowledge.

“The day science begins to study non-physical phenomena, it will make more progress in one decade than in all the previous centuries of its existence.” ― Nikola Tesla.

Ptolemy to Galileo: Musical Reflections on the Heliocentric Revolution

In critiquing the tropical zodiac championed by Ptolemy, it is illuminating to draw upon the lyrics of “Ptolemy Was Wrong” by The Ocean Collective. This song poignantly captures the anguish and revelation experienced by early astronomers like Galileo and Copernicus upon discovering that the geocentric model fails to explain celestial phenomena such as the phases of Venus.

The lyrics begin with a stark confession: “I can tell you what I’ve seen , I can no longer believe.” This echoes the transformative realization that the Earth-centered model is fundamentally flawed. The astronomer’s observations lead to an undeniable conclusion: “If Venus shows all phases like the moon , The earth must revolve ’round the Sun.”

The song further explores the emotional turmoil and isolation that often accompanies such groundbreaking discoveries. The line “But no one will believe me” reflects the resistance met by proponents of the heliocentric model in their time. This was particularly true for Galileo, who faced significant opposition from the Catholic Church. His advocacy for the heliocentric model led to a trial by the Roman Inquisition, resulting in his forced recantation and subsequent house arrest.

The repeated refrain, “It’s like nothing, Like nothing I’ve seen was for real,” conveys the profound shift in perspective that occurs when one moves from false beliefs to contradictory truths. This transition is not just a shift in understanding but a complete upheaval of one’s worldview, a turmoil Galileo personally endured as he was isolated and silenced for his scientific truths.

Ultimately, the lyrics highlight a critical truth about scientific progress: “I raised my eyes, Up high toward the night sky… But I found the watchmaker was blind.”. The “blind watchmaker” here is a powerful metaphor for Ptolemy, who meticulously crafted his geocentric model of the universe yet turned a blind eye to the mounting evidence that contradicted it.

The song “Ptolemy Was Wrong” poignantly reminds us that progress in science often requires breaking free from established doctrines and embracing new evidence, even when it contradicts long-held views. The emotional and professional isolation experienced by those like Galileo and Copernicus is a testament to the difficulties faced by pioneers of groundbreaking ideas. Their struggles highlight the importance of maintaining scientific integrity and openness to new paradigms, ensuring that the pursuit of knowledge remains unimpeded by dogma.

In reflection, the heliocentric revolution not only redefined our understanding of the cosmos but also set a precedent for the importance of authentic scientific inquiry. The transition from Ptolemy’s geocentric model to the heliocentric view championed by Copernicus and Galileo marks a pivotal shift in the history of science—a shift that reminds us of the value of questioning established norms and the courage required to embrace the unknown.

The song’s exploration of this theme resonates deeply with the historical context in which it is set. The transition from the Ptolemaic to the Copernican system was not just a scientific revolution but also a profound cultural and philosophical shift. It required a willingness to question long-held beliefs and to embrace new, often unsettling, truths.

Galileo’s telescopic observations and Copernicus’s mathematical models provided compelling evidence for heliocentrism, but acceptance of these ideas was slow and met with significant resistance from both the scientific community and religious authorities. Galileo’s house arrest symbolizes the personal and professional risks taken by these pioneering astronomers. The emotional weight of these discoveries, as captured in the lyrics, reflects their courage and resilience.

In essence, “Ptolemy Was Wrong” by The Ocean Collective not only critiques the inaccuracies of the geocentric model but also celebrates the bravery of those who dared to challenge it. The song serves as a reminder of the ongoing journey of scientific inquiry, where each generation builds upon the insights and corrections of the previous one.

The metaphor of the blind watchmaker invites us to reflect on our own potential blind spots and to remain vigilant in our pursuit of knowledge, always ready to revise our understanding in light of new evidence. This metaphor suggests that the universe operates on principles that are indifferent to our beliefs or desires.

To move forward, one must embrace evidence and reason, even if it means discarding long-held beliefs. The song’s message resonates deeply with the scientific journey of questioning, observing, and ultimately, accepting the truth, regardless of how uncomfortable it might be.

“To be Jedi is to face the truth, and choose. Give off light, or darkness, Padawan. Be a candle, or the night.” – Yoda.

The Enduring Legacy of Jyotish and the Sidereal Zodiac: Maintaining Astronomical Precision

Vedic astrology, esteemed as an eternally accurate celestial map, utilizes the sidereal zodiac, which functions as a steadfast, timeless celestial clock. This enduring system guarantees unparalleled astronomical precision, guiding individuals with the wisdom of the stars.

This meticulous adherence to the positions of celestial bodies is a testament to the sophisticated mathematical models and precise astronomical observations developed by ancient Indian sages over 5,000 years ago. In India, astrology is not merely a mystical belief system but a deeply revered discipline that intertwines spirituality with scientific rigour, influencing various aspects of life, from personal decisions and religious rituals to cultural practices and societal norms. The Indian government officially endorses a nationally accepted ‘ayanamsha’ to account for the precession of the equinoxes, ensuring a nationally standardized astronomical precision in astrological calculations.

The enduring respect for Jyotish (Vedic astrology) in India highlights a cultural continuity that deeply values ancient wisdom and its practical applications. Unlike Western tropical astrology, which has drifted from its astronomical roots and faces skepticism, Vedic astrology’s use of the sidereal zodiac maintains a timeless and unbroken connection to the cosmos. This difference highlights a broader cultural divergence in the perception and practice of astrology. In the West, astrology is often relegated to entertainment or dismissed entirely by many, but in India, it remains an integral part of a rich heritage of spiritual and scientific traditions. This reverence for astrology as a timeless and precise reflection of the stars ensures its continued relevance and respect in Indian society.

Furthermore, the preservation of this knowledge over millennia without distortion or corruption is a remarkable feat, showcasing the dedication to accuracy and the profound understanding of the cosmos by ancient Indian scholars. As a result, astrology in India remains a living tradition, respected not only for its spiritual significance but also for its scientific foundation, bridging the ancient with the modern and continuing to guide countless individuals in their daily lives.

Why the Source of Knowledge Matters: Authenticity and Integrity in Astrology

Astrology, as a spiritual science, requires a deep understanding of the spiritual energy that underpins the two systems of astrology to truly grasp their authenticity and profound nature. Much like how a chef imparts their passion into a dish, an artist imbues their spirit into their artwork, or a carpenter crafts their essence into their woodwork, every creation bears the imprint of its creator’s energy. Understanding the foundation, source, or root of any knowledge and wisdom is profoundly significant because it allows one to appreciate the context, authenticity, and spiritual depth from which the information emanates.

When we contemplate the origin of knowledge, we must assess not only the analytical or intellectual abilities of the source but also the spiritual evolution and integrity of the individuals behind it. This holistic approach ensures that the wisdom we embrace is pure, untainted, and aligned with higher truths.

Modern Western astrology, while distinct in its approach and interpretations, shares foundational elements with Hellenistic astrology, particularly the use of the tropical zodiac. The Hellenistic period arose from the tumultuous conquests of Alexander the Great. This era, marked by the blending of Greek, Egyptian, Babylonian, and other traditions, was also shadowed by violence and the cost of countless human lives.

While Alexander the Great did not directly create or practice Hellenistic astrology, his conquests and the cultural integration they fostered were crucial in birthing the conditions that allowed Hellenistic astrology to develop and flourish. His role in establishing centres of learning and promoting the exchange of knowledge across diverse cultures was instrumental in the birth and evolution of this astrological tradition.

The figure of Claudius Ptolemy looms large in this historical backdrop. Western astrology, heavily influenced by the works of Ptolemy, has been critiqued for its reliance on the tropical zodiac. Ptolemy himself is a controversial figure, accused of fraud and plagiarism, which raises questions about the legitimacy and spiritual grounding of the knowledge he propagated.

In stark contrast, the sidereal zodiac used in Vedic astrology, or Jyotish, finds its origins in the ancient Vedas, texts believed to be divinely revealed to enlightened sages through profound meditation. This sacred knowledge, emanating from spiritually evolved individuals, carries with it an unparalleled purity and depth. The sidereal zodiac aligns with the actual constellations in the sky, ensuring that it remains accurate and in harmony with the cosmic rhythms. The wisdom of Jyotish is imbued with a sense of divine purpose, fostering genuine understanding and resonance with higher truths.

By recognizing and valuing the spiritual nature of the sources of our knowledge, we can embrace wisdom that transcends the mundane and connects us to the cosmos. The roots of our understanding matter deeply. They shape not only the accuracy of our interpretations but also the integrity and authenticity of our spiritual journeys.

The Two Trees

In a mystical grove, two trees stand side by side, their roots digging deep into the soil of human consciousness.

The Tree of Enlightenment

The first tree, a venerable sentinel of Vedic sidereal wisdom, exudes an aura of serene divinity. Its roots intertwine with the sacred texts of the ancient Vedas, drawing nourishment from the pure, untainted wellspring of divine revelation. This tree’s trunk is imbued with the resilience of timeless truths, and its branches are laden with fruits that shimmer with an otherworldly light. Each fruit is a gem of celestial knowledge, offering insights that are not only precise and harmonious but also deeply resonant with the cosmic rhythms that govern the universe.

The Tree of Illusion

In contrast, the second tree, born of the Hellenistic Western tropical tradition, has roots that pulse with an uneasy energy, tainted by the shadows of conquest, violence, and controversy. Its trunk, though strong, bears the marks of intellectual strife, celestial distortion and spiritual dissonance. Its branches stretch towards the sky in a quest for validation. The fruits it yields appear sweet and enticing but often carry a bitter aftertaste of astronomical inaccuracy.

As we stand between these two trees, we are invited to partake in the fruits they offer. The choice we make is more than a mere preference; it is a reflection of our deepest values and aspirations.

Cosmic Choices: Organic or Artificial?

The celestial ballet of stars and planets has captivated human curiosity for millennia, guiding sailors across treacherous seas and inspiring poets to ponder their place in the universe. Among the myriad systems to interpret the heavens, the sidereal and tropical zodiacs stand as two distinct paradigms.

The sidereal zodiac, deeply rooted in the observable positions of constellations, is comparable to an organic crystal formed in the depths of the Earth. It is a natural manifestation, unerring and timeless, reflecting the true celestial coordinates that have guided ancient sages and star-gazers alike.

In contrast, the tropical zodiac, often perceived as an artificial construct, resembles a synthetic crystal, fashioned in the controlled environment of a laboratory. This system, based on the Earth’s seasons and the equinoxes, diverges from the actual constellations’ positions over time due to the precession of the equinoxes. While the intent is to align with the Earth’s cyclical rhythms, it inevitably drifts from the sidereal positions, leading many to view it as an artificial interpretation of the celestial alignments. This divergence fuels the debate: does the tropical zodiac’s convenience and alignment with terrestrial seasons justify its deviation from the sidereal truth?

Much like the intrinsic beauty and potency of a natural crystal, the sidereal zodiac’s alignment with the constellations offers an unadulterated glimpse into the cosmos. It resonates with those who seek authenticity, embracing the celestial order as it appears in the night sky.

Ultimately, one doesn’t need to perform extreme mental gymnastics to discern which zodiac holds more truth. A simple step outside on a clear night, armed with an app like SkyView, allows anyone to see which constellation graces the background of the planets.

The real choice lies in deciding whether to trust the evidence of one’s own eyes and the cosmic display above or to adhere to the mainstream, artificial construct of the tropical zodiac.

The sky itself offers a testament to the enduring dance of the stars, inviting each of us to decide which narrative we choose to embrace.

The choice between them often reflects one’s philosophical leanings—whether one yearns for the organic, untamed truth of the stars, or the seasonal narrative crafted by human hands.

A Harmonious Approach: Integrating the Sidereal Zodiac into Western Astrology

For those who follow Western tropical astrology, this article isn’t suggesting delving into Vedic astrology unless one feels particularly drawn to it. Rather, the idea is to consider incorporating the sidereal zodiac into Western practice. While modern Western astrology has its roots in Hellenistic traditions, it has developed its own unique approach.

Both Vedic and Western astrology have evolved independently, each with distinct methodologies, interpretations, and cultural significance. The proposal to integrate the sidereal zodiac is not about merging these two systems into one. Instead, it seeks to create a harmonious approach by using a common astronomical framework.

This integration could lead to more precise alignments and interpretations, fostering a deeper understanding of astrological influences without compromising the unique aspects of either tradition. Moving from the tropical to the sidereal zodiac is not an ‘end’ but rather a rebirth into a new understanding. It presents an opportunity for enthusiasts of Western astrology to expand their horizons and embrace a different perspective. This transformation can be viewed as an evolution, enriching one’s practice with a fresh, yet astronomically grounded, approach to astrology.

The sidereal zodiac offers a way to reconnect with the stars in their true positions, providing a more accurate reflection of cosmic energies. This rebirth is not about abandoning the familiar but about enhancing one’s astrological journey with new insights and perspectives, paving the way for a more integrated and holistic understanding of the cosmos.

As Moby reminds us in his song, “We Are All Made of Stars”:

“Growing in numbers

Growing in speed

I can’t fight the future

Can’t fight what I see

‘Cause people, they come together

People, they fall apart

And no one can stop us now

‘Cause we are all made of stars.”

These lyrics encapsulate the essence of our cosmic connection and the continuous evolution of our understanding, illustrating that our journey through the stars is both a personal and collective experience.

Reconnecting with the Cosmos

In the distant past, our ancestors lived with a profound connection to the cosmos, their lives illuminated by the celestial ballet above. For them, astrology and astronomy were not separate disciplines but intertwined like the harmonious dance of the sun and moon. The night sky was a vast, awe-inspiring canvas that guided their understanding of the world and their place within it.

Today, however, many modern astrologers have traded the wonder of that expansive night sky for the confines of screens and software. Technology has granted them the remarkable ability to focus on interpretation, guidance, and predictions by providing instant access to intricate charts and data. Yet, this convenience has come at a cost. The reliance on digital tools has inadvertently diminished the significance of direct astronomical observation. In the past, astrologers were also astronomers, their practices deeply intertwined as they observed the heavens to derive insights. Now, the necessity for astrologers to engage directly with the night sky has waned, and with it, the art of stargazing has become less central to the practice of astrology.

This shift has led to a disconnect from the actual celestial sphere, overshadowing the awe-inspiring relationship between the cosmos and astrology with technological convenience. Many astrologers today lack proficiency in astronomy, focusing more on the symbolic interpretations of charts than on the celestial mechanics that govern the universe.

But to truly honour the wisdom of the ancients, we must lift our gaze back to the heavens. For we are all composed of stardust, born from the same cosmic materials that make up the stars themselves. Embracing the sidereal zodiac is not just a return to astronomical accuracy but a reconnection to our celestial origins. On starry nights, as we marvel at the universe above, we receive more than data; we receive transmissions of celestial energy that allow us to connect with the cosmos on a deeper level.

In these moments of stargazing, we do more than observe; we become part of a grand, cosmic narrative, written in the stars and waiting to be rediscovered. Each twinkling light is a whisper from the universe, a reminder that we are not isolated beings but integral parts of a vast, interconnected whole. Through these celestial dialogues, we find more than knowledge; we find a sense of belonging, a timeless connection to the mysteries of the cosmos that our ancestors once knew so well.

As we ponder the cosmic wisdom of the ancients and the celestial dance above, it’s almost as if the universe is playfully nudging us, like a parent saying, “Put down that phone, get off your digital star maps, and go out to play under the real stars—because no app or software can beat the original night sky experience!”

A Journey Through Space and Time

This is the story of our magnificent universe, a realm of wonders that stretches far beyond our wildest dreams.

The universe stands as an infinite expanse of beauty and enigma, stretching beyond our imagination and encompassing billions of galaxies. This enchanting creation mesmerizes us with the fact that there are more galaxies than there are grains of sand on all the Earth’s beaches. Each galaxy is a universe in itself, brimming with innumerable stars and planetary systems, hinting at the boundless possibilities of other worlds and alien skies.

Zooming in, we find our cosmic neighbourhood includes Andromeda, a majestic spiral galaxy hurtling towards us on a collision course set to merge with our own Milky Way in billions of years. This inevitable union will create an even more magnificent galactic panorama.

This illustration shows a stage in the predicted merger between our Milky Way galaxy and the neighboring Andromeda galaxy, as it will unfold over the next several billion years. In this image, representing Earth’s night sky in 3.75 billion years, Andromeda (left) fills the field of view and begins to distort the Milky Way with tidal pull.

Our home, the Milky Way, is an awe-inspiring barred spiral galaxy, a breathtaking masterpiece of stars, planets, and enigmas waiting to be uncovered. It features a central bar-shaped core from which elegant spiral arms stretch out. These arms act as cosmic highways, with our Solar System nestled within one of them—the Orion Arm, located around 27,000 light-years away from the Galactic centre.

The Galactic Centre is the central region of a galaxy and houses an immense collection of older stars and a supermassive black hole named Sagittarius A*. This colossal black hole exerts a dominating gravitational force, choreographing the stellar dance and shaping the fate of our galaxy.

Within the Orion Arm, our Sun, an average-sized star, shines brightly, accompanied by its family of planets, including our beloved Earth. The gravitational pull of the Sun keeps these planets in motion, ensuring that Earth sustains the delicate equilibrium necessary for life.

However, our Sun is not stationary; it hurtles through space, orbiting the Galactic centre at an astonishing speed of approximately 828,000 kilometres per hour (514,000 miles per hour). As the Sun orbits the Galactic centre, it takes around 230 million years to complete one orbit, a period known as a cosmic year or Galactic year.

As we narrow our focus to Earth, our home planet, we find it uniquely positioned within the Solar System to support life. The night sky above Earth is a canvas of ancient stories and celestial patterns identified by ancient civilizations. Currently, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) officially acknowledges 88 constellations.