Part III Overview

Part III begins with an exploration of the timeless wisdom encapsulated in the Vedas, where ancient sages acted as guardians of divine knowledge, ensuring its preservation through the oral traditions of the Gurukul system -often likened to the Hogwarts of ancient India. The section emphasizes the vibrational essence of correct pronunciation in Sanskrit, a linguistic marvel that carries spiritual significance. This section then delves into the Sidereal Zodiac, which, with its astronomical precision, mirrors the principle of “as above, so below.” The Nakshatras, described as the eternal language of the stars, form a Vedic celestial clock that intricately weaves both solar and lunar cycles, offering a detailed celestial timetable that reflects the movements of the sun and moon across the sky. The discussion extends to the Galactic Centre and the mystical significance of the number 108, further enriching the cosmic tapestry.

The origins of zodiac signs are then examined, a topic that has sparked much debate regarding whether they are rooted in Babylonian or Vedic traditions. This inquiry invites reflection on the nature of history and its authors, as written evidence does not always reveal the true origins, especially given Vedic astrology’s initial oral tradition. A closer examination, particularly the harmonious integration of Nakshatras and zodiac signs, suggests that zodiac signs have Vedic origins—an alignment comparable to the “Cinderella Effect,” where the fit is perfect and undeniable.

The sidereal wheel is revealed as the original and perfect system, in contrast to the later tropical wheel that is astronomically flawed—a reimagining similar to the classic example of reinventing the wheel, often yielding less effective outcomes.

The concept of Ayanamsha is explored, presenting the precession puzzle and the intricacies of determining 0 degrees Aries. This pursuit, reminiscent of the quest for the precise values of Pi and the Golden Ratio, suggests a mystical science that transcends conventional understanding.

The discussion concludes with a look at ancient Indian texts on astrology, recognized as some of the earliest written records that comprehensively outline the principles of Vedic astrology, including the Rig Veda and Vedanga Jyotisha. The Rig Veda’s hymns poetically address advanced concepts such as heliocentricity, the Big Bang theory, and eclipses, as well as the division of the year into twelve months and the week into seven days.

The journey concludes with insights from the Brihat Parashara Hora Shastra, where the initial verses lay out the essential ethical and spiritual qualities required for both the teacher and the student in the pursuit of astrological wisdom.

Timeless Wisdom of the Vedas

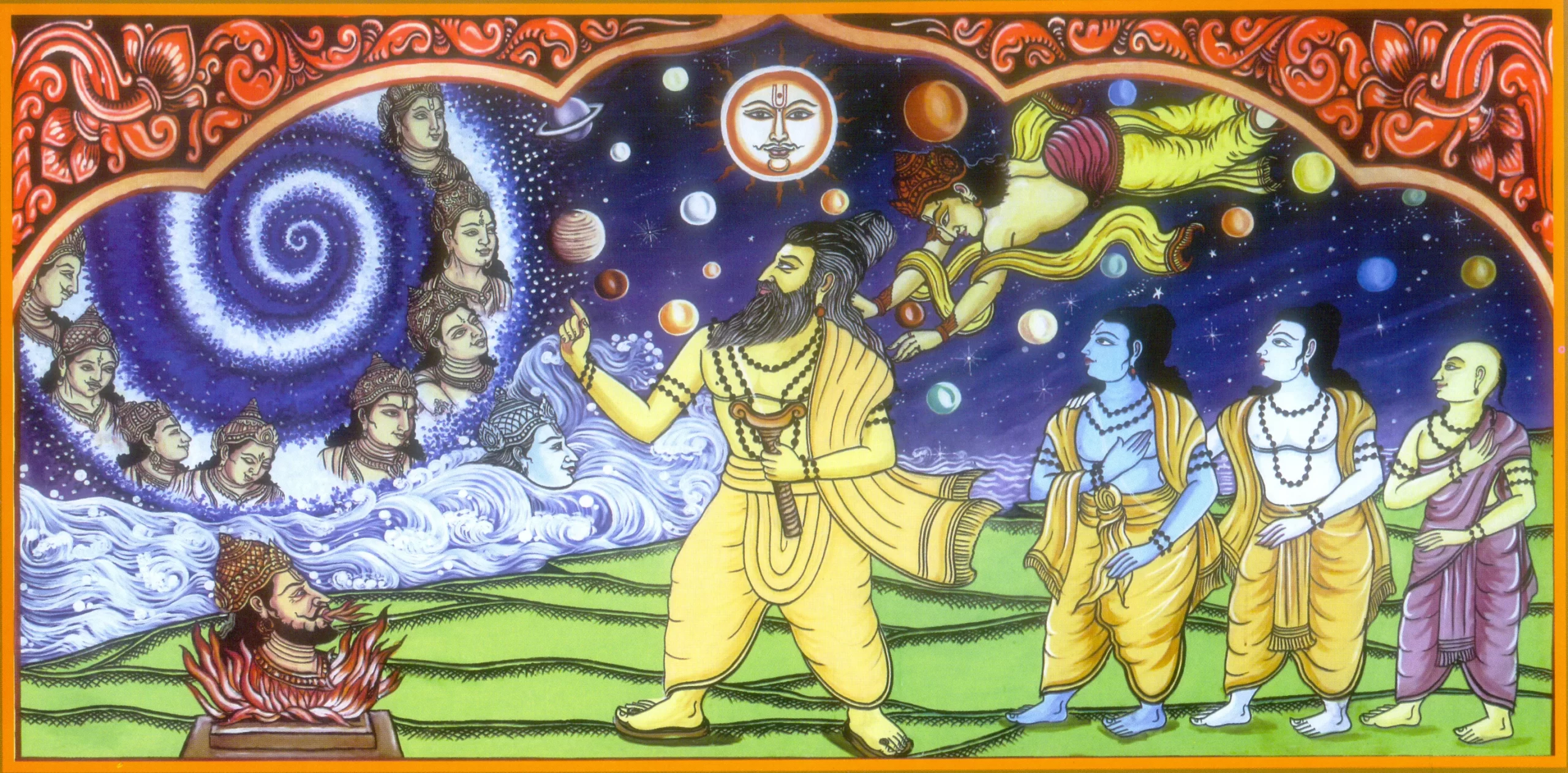

In the tranquil forests and serene mountains of Ancient India, profound silence often enveloped the meditative retreats of revered sages known as Rishis. These wise men dedicated their lives to deep spiritual practices and the pursuit of ultimate truth. Through rigorous meditation, they sought to transcend the physical realm and connect with higher consciousness. It was in these moments of profound stillness that they channeled the wisdom of Brahma, the creator deity of the universe. This divine knowledge would shape the very foundation of Sanātana Dharma (सनातन धर्म), meaning “eternal dharma” or “eternal order.”

The Vedas are considered apauruṣeyā, meaning “not of a man, superhuman” and “impersonal, authorless.” This term highlights their divine origin, signifying that the Vedas were not created by humans but were divine revelations perceived by the Rishis. Through deep meditation and heightened states of consciousness, these sages were able to tap into universal truths and encode them into hymns or mantras. The hymns within the Vedas are articulated in Sanskrit, one of the world’s most ancient languages.

The Vedas are timeless and eternal, believed to be the fundamental source of all knowledge. These mantras encompass a vast array of profound topics, including cosmology, the nature of existence, metaphysics, and the intricate workings of the human mind and spirit. Each mantra is revered as a sacred sound vibration, often referred to as primordial sounds, considered to possess the power to invoke divine energies and facilitate a deeper connection with ultimate reality.

The Vedas are divided into four main collections: Rigveda, Samaveda, Yajurveda, and Atharvaveda.

Each collection contains hymns, prayers, rituals, and philosophical discourses that reflect the holistic nature of Vedic knowledge. Among these, the Rigveda is the oldest and contains hymns that are particularly rich in cosmological and astronomical references. The Vedas also include the Vedangas, auxiliary disciplines that support the understanding and practice of Vedic teachings. Among these, Jyotisha Vedanga is the Vedic astrology and astronomy discipline.

Astronomy, as a branch of knowledge, was intricately woven into the fabric of Vedic wisdom. The ancient seers observed the movements of celestial bodies and recorded their findings in hymns and verses, which served as both spiritual and practical guides. They understood the cyclical nature of time, the phases of the moon, the positions of the planets, and the changing seasons, integrating these observations into their rituals and daily lives. These astronomical insights were not just scientific observations but were seen as reflections of the cosmic order, mirroring the eternal principles that governed the universe.

In essence, astronomy was an integral part of the vast knowledge encapsulated in the Vedas. It was not merely a scientific pursuit but a spiritual one, aimed at understanding the divine order of the cosmos. The study of stars and planets was considered a subset of the greater Vedic wisdom, providing a celestial map to navigate both the physical and metaphysical realms.

The Rishis meticulously observed the cosmos, they charted the movements of celestial bodies, developing sophisticated mathematical models that formed the basis of Vedic astrology or Jyotish. These sages were the vessels through which the sacred Vedas were brought to humanity.

The Integral Role of Oral Transmission in Ancient Vedic Education

The Vibrational Essence: Spiritual Significance of Correct Pronunciation

In ancient times, the knowledge of the Vedas was transmitted orally in Sanskrit for centuries before it was ever written down. The advent of writing in the Bronze Age marked a significant milestone in human history, but it came relatively late compared to the oral traditions that had been practiced for millennia. This method of transmission through meticulous oral recitation was not merely a means of preserving words but also the precise sounds, intonations, and rhythms essential for the correct pronunciation of hymns, mantras, and other spiritual teachings. To ensure this precision, elaborate mnemonic techniques were employed, allowing the Vedas to be preserved with remarkable accuracy over generations.

In ancient India, the system of education known as the Gurukul was instrumental in this oral tradition. Gurukul schools were residential setups where students, or shishyas, lived with their teacher, or guru, in a close-knit community. The gurus imparted knowledge orally, emphasizing the importance of correct pronunciation and memorization of the texts. This focus on oral learning ensured that students developed a deep understanding and reverence for the Vedas, maintaining the integrity of these sacred scriptures. The rigorous training in these schools included the practice of chanting and reciting the hymns and mantras accurately, as the vibrational quality of the sounds had spiritual significance.

The importance of oral learning in ancient times cannot be overstated. The ability to pronounce words correctly was crucial, especially for hymns and mantras, as it was believed that the efficacy of these spiritual practices depended on the precise articulation of sounds. Oral memory, the practice of passing knowledge verbally from one generation to another, has been a cornerstone of human culture. This method relied on the human ability to remember and recount information accurately, with communities preserving vast amounts of knowledge through collective memory and skilled storytellers. Even today, the legacy of this oral tradition can be seen in various indigenous cultures around the world, where oral memory remains a vital way to preserve and transmit cultural heritage.

Gurukul – The Hogwarts of Ancient India

Imagine a Gurukul as an ancient, mystical Hogwarts nestled in the serene mountains of India. Much like the famed school of witchcraft and wizardry, this sacred educational haven was where young aspirants, or shishyas, gathered under the tutelage of wise gurus. Instead of wands and spells, the students at the Gurukul mastered the timeless wisdom of the Vedas through rigorous meditation, precise chanting, and deep spiritual practices. The air buzzed with the incantations of magic, with the sacred vibrations of ancient mantras, believed to connect the physical realm to higher consciousness.

Within this enchanted setting, the gurus, much like the sagacious Dumbledore, imparted their divine knowledge through oral traditions, ensuring each syllable and intonation was preserved with the utmost precision. The Gurukul’s serene environment, woven with the fabric of the cosmos and the eternal order of Sanātana Dharma, was a place where the mysteries of existence and the nature of the universe were explored.

The Gurukul schools were not just places of learning but sanctuaries where students embarked on a spiritual quest, guided by their gurus, much like young wizards discovering their destinies. Here, the pursuit of ultimate truth and self-discovery was paramount, echoing the timeless journey of spiritual enlightenment.

The Gurukul tradition thrived for millennia, a beacon of ancient wisdom and spiritual enlightenment. For thousands of years, this sacred educational system cultivated the minds and souls of young aspirants, embedding in them the profound teachings of the Vedas, Upanishads, and other sacred texts. These institutions, interwoven with the very essence of Indian culture and spirituality, nurtured generations of scholars, philosophers, and spiritual leaders within their tranquil, natural settings. The ethos of the Gurukul was built on the principles of holistic education, where the mind, body, and spirit harmoniously developed under the guidance of enlightened gurus.

However, the British colonial rule in India systematically dismantled the Gurukul system, aiming to impose Western education models and erode indigenous knowledge. The British introduced policies that marginalized traditional Indian education, favoring English-language schools that focused on creating a class of clerks and administrators to serve the colonial machinery. The British aimed to supplant Indian education with their own, believing their culture and language to be superior.

Thomas Babington Macaulay, a British historian and politician, notoriously stated, “A single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.” This mindset led to the establishment of an education system that prioritized English texts over indigenous knowledge, thereby eroding traditional Indian educational practices and institutions.

The rich legacy of oral traditions, spiritual exercises, and holistic learning methods inherent to the Gurukul system was undermined, leading to the gradual decline of these ancient institutions. Despite the systematic efforts to obliterate this profound legacy, the echoes of the Gurukul’s wisdom resonated through the hearts and minds of the Indian people, preserving its essence against the tides of change.

In modern times, the resilient spirit of the Gurukul tradition endures, adapting and evolving to contemporary contexts. Many educational institutions today draw inspiration from the Gurukul model, integrating holistic approaches and emphasizing spiritual and moral education. The timeless wisdom of the Vedas and ancient Indian philosophy continues to influence contemporary thought, highlighting the resilience of this rich cultural heritage. Like the enduring magic of Hogwarts, Gurukul’s legacy perseveres, a testament to the indomitable spirit of ancient knowledge that transcends time, nurturing the pursuit of truth and self-discovery for future generations.

The Sanskrit Effect: A Linguistic Marvel and Cognitive Booster

Sanskrit, often revered as the “language of the gods,” earns this title due to its divine origins in Hindu mythology, where it is believed to be the language spoken by deities. It stands as a linguistic masterpiece with its intricate grammar and phonetic precision. The Vedas, a collection of ancient texts, were encoded in Sanskrit as the rishis channeled knowledge from the creator deity Brahma. Its extensive vocabulary and nuanced syntax allow it to convey profound philosophical concepts succinctly. The phonetic system of Sanskrit mirrors the natural rhythm and vibrations of the human body, making the recitation of Sanskrit mantras a spiritually enriching experience.

The Ancient Code

If Sanskrit were a piece of software, it would be the ultimate masterpiece of coding from the ancient world. With its impeccable syntax and endless loops of phonetic precision, it’s the original programming language—minus the bugs and tech support. Just like a well-structured code, Sanskrit’s grammatical rules are as airtight as a developer’s dream, allowing its users to execute complex ideas with the elegance of a perfectly compiled program. So, next time you chant a mantra, remember: you’re basically debugging your brain, one syllable at a time!

The Cognitive Benefits of Sanskrit

Recent neuroscientific studies have uncovered a captivating phenomenon known as the “Sanskrit Effect.” Research indicates that children who recite Sanskrit mantras develop highly advanced brains, especially in areas related to memory, attention, and cognitive function. The practice of memorizing and reciting complex Sanskrit texts enhances the brain’s ability to process and retain information. Engaging with the phonetic precision and rhythmic patterns of Sanskrit has been linked to improved performance in problem-solving, analytical thinking, and even speech therapy. The repetitive and structured nature of Sanskrit recitation is believed to promote neuroplasticity, enhancing the brain’s capacity to adapt and learn.

Lessons from Ancient Scholars

This heightened cognitive development is particularly noteworthy in today’s generation, where ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) is common and the reliance on note-taking and digital aids is widespread. In contrast, ancient Indian scholars are celebrated for their extraordinary mental abilities, demonstrated through their capacity to orally recall extensive texts with precision. This remarkable oral memory is not only a testament to their intellectual capabilities but also to their deep commitment and rigorous training. In an era dominated by distractions, these traditions offer a beacon of focus, memory, and mental discipline.

Safeguarding Sacred Knowledge through Oral Traditions

Just as a password is better stored in memory than written down to protect it from misuse, Vedic knowledge has traditionally been passed down through oral traditions to safeguard its sacredness and integrity. This oral transmission ensured that Vedic knowledge remained within the trusted circle of knowledgeable individuals who could faithfully preserve its purity and meaning.

Oral traditions serve as a living repository of wisdom, much like a password securely held in one’s mind. Through rigorous training and disciplined practice, Vedic scholars memorized and recited complex scriptures, ensuring that every syllable and intonation was accurately conveyed. This meticulous process protected the knowledge from being adulterated or lost in translation or written records, embedding it deeply within the cultural and spiritual ethos of the community.

Furthermore, Vedic knowledge was imparted to dedicated students through direct transmission from teacher to pupil, fostering a personal connection and a deep sense of responsibility in the custodian of the knowledge. This method ensured that sacred knowledge was preserved, respected, and passed down through generations with the reverence and integrity it deserved. The oral tradition acted as a guardian, maintaining the sanctity and continuity of these ancient teachings.

The Dual Purpose of Vedic Riddles

The Vedas are indeed brimming with profound truths that often reveal themselves through cryptic and riddle-like hymns. Much like the enigmatic wisdom of Yoda from Star Wars, the Vedic hymns challenge readers to delve deeply into their meanings, urging a contemplation that goes beyond the literal. These texts, composed in a poetic and metaphorical language, have layers of interpretation that scholars have been unravelling for centuries. The timeless nature of the Vedas ensures that their wisdom remains relevant across ages, echoing the enduring teachings of the wise sages.

In Vedic literature, the cryptic nature of the hymns serves a dual purpose: it preserves the esoteric knowledge for those who seek it earnestly and stimulates intellectual and spiritual growth. This dual purpose is similar to a spiritual sieve, filtering out those who are not yet ready for the deeper truths while encouraging genuine seekers to embark on a path of rigorous inquiry and self-reflection. The wisdom of the Vedas, much like Yoda’s teachings, encourages a journey of self-discovery and enlightenment, where the seeker must navigate the riddles to uncover the deeper truths hidden within.

Moreover, the Vedas also function as a guide for ethical and moral conduct, much like Yoda’s counsel to the Jedi. They provide a framework for living a life in harmony with the cosmos, emphasizing values such as truth, righteousness, and compassion. By engaging with these texts, individuals are not only challenged intellectually but also transformed ethically and spiritually.

The Vedas, therefore, serve as a holistic manual for life, guiding seekers towards both personal enlightenment and societal harmony, much like the wise Yoda who teaches not just mastery of the Force, but also wisdom, patience, and humility.

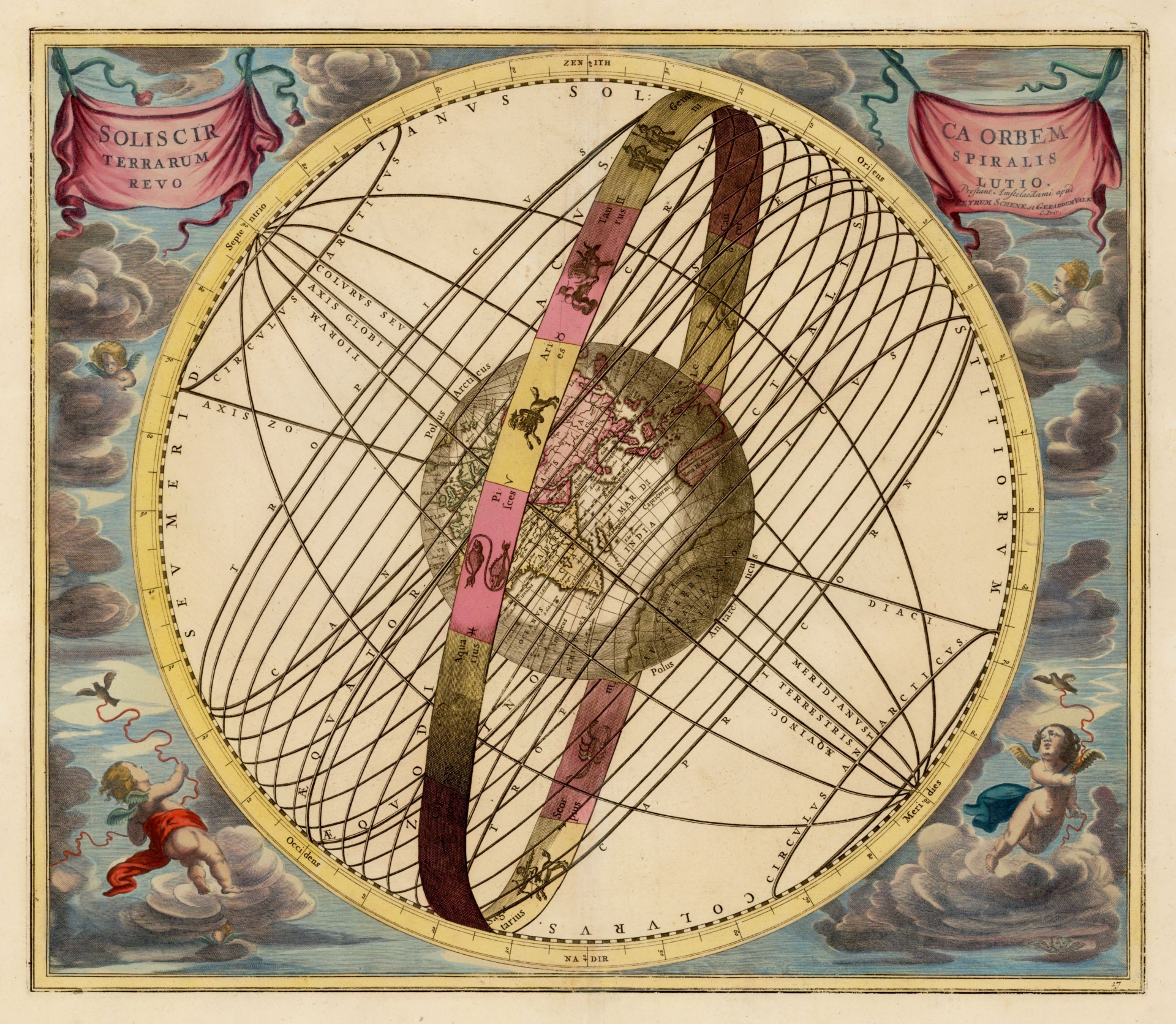

The Sidereal Zodiac – As Above, So Below

Vedic astrology offers a comprehensive understanding of both the sidereal and tropical zodiacs. The Tropical Zodiac is known as the Sayana zodiac, while the Sidereal Zodiac is referred to as the Nirayana zodiac.

The term Sayana means “with motion,” reflecting the Tropical zodiac’s gradual shift away from the stars over time. Conversely, Nirayana is derived from “nir” (without) and “ayana” (motion), indicating that the Sidereal zodiac is fixed relative to the stars.

In English, the term “sidereal” originates from the Latin word sidereus, meaning “of the stars.” The sidereal zodiac is a system that aligns the true positions of celestial bodies with the fixed stars and constellations. Unlike the tropical zodiac, the sidereal zodiac takes into account the actual positions of constellations in the sky, making it astronomically accurate and grounded in the cosmic order.

The sidereal zodiac connects Earth to the constellations by accounting for the precession of the equinoxes. This alignment offers a more precise reflection of our relationship with the cosmos, embodying the ancient principle of “as above, so below.”

On a grander scale, the sidereal zodiac is intimately connected to the movement of our Solar System within the Milky Way galaxy, maintaining Earth’s relationship to the Galactic Center. Our Sun, along with its planetary companions, revolves around the Galactic Center, completing one orbit roughly every 225-250 million years.

This cosmic journey highlights the dynamic and interconnected nature of the universe. By accounting for the precession of the equinoxes and maintaining an accurate relationship between the Earth and the stars, the sidereal zodiac reflects the ever-changing yet harmonious dance of celestial bodies. This reinforces our intrinsic link to the cosmos and highlights the profound interconnectedness of all existence.

Historical Context and Development

The concept of the sidereal zodiac, also known as the Nirayana system in Indian astrology, is deeply rooted in the history of ancient Indian astronomy and astrology. The ancient Indian text, Vedanga Jyotisha, dating from approximately 1200 BCE to 800 BCE, laid the foundational framework for this astronomical concept.

As one of the six Vedangas—auxiliary disciplines associated with the Vedas—Vedanga Jyotisha primarily focuses on timekeeping and the calendrical calculations necessary for performing Vedic rituals. The text emphasizes the movements of celestial bodies, such as the Sun, Moon, and planets, highlighting their significance in determining auspicious times for religious ceremonies.

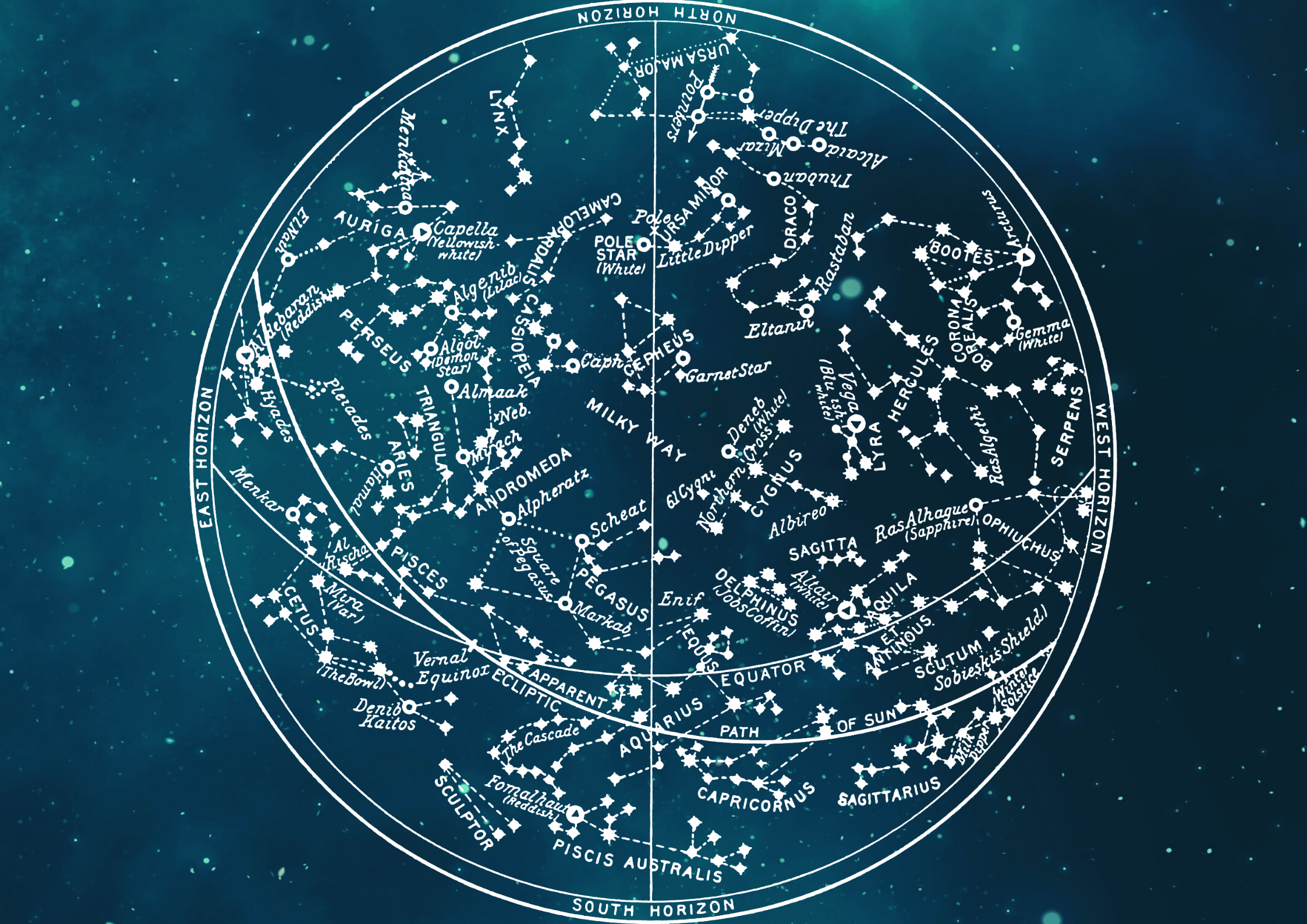

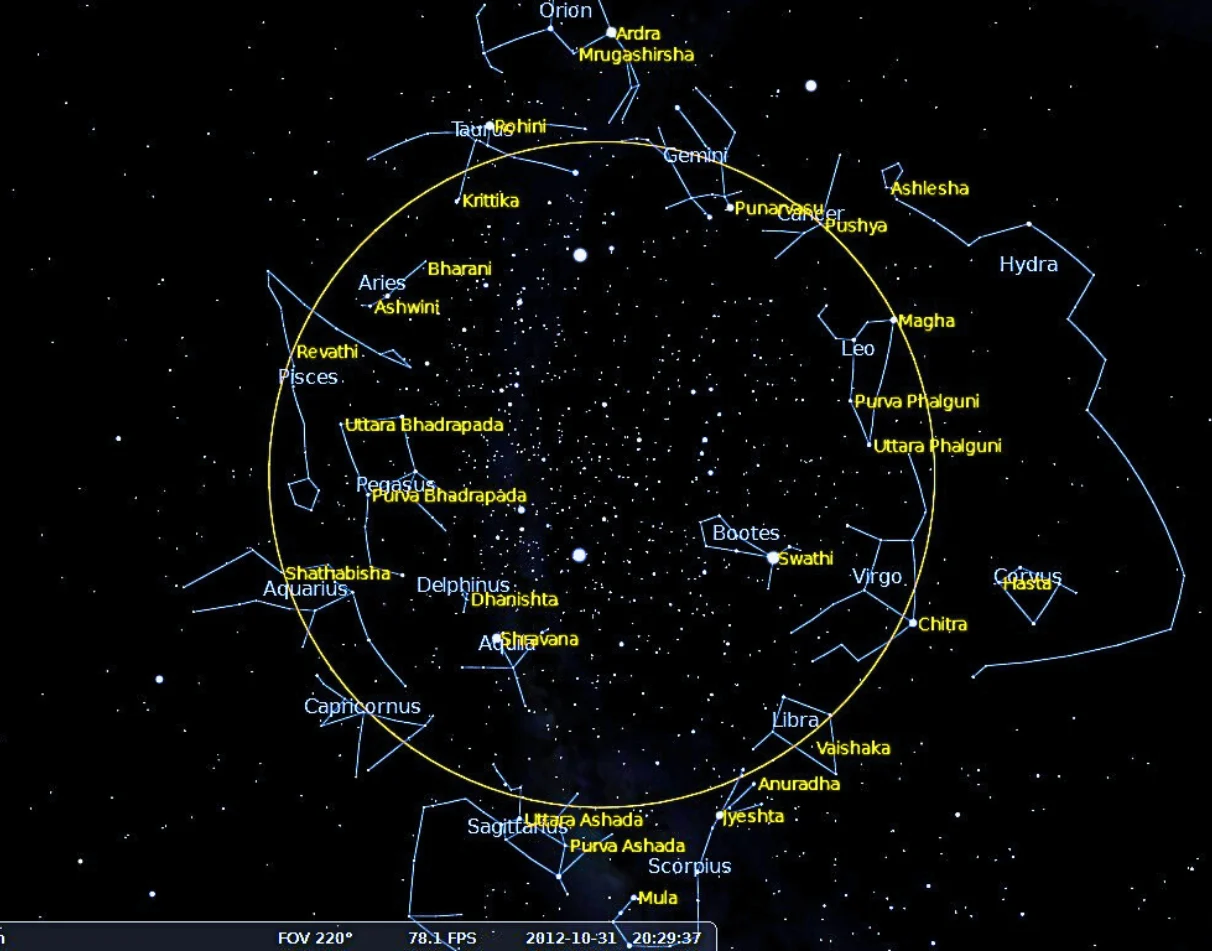

Vedanga Jyotisha provides evidence of early astronomical knowledge through its discussions on celestial movements and its detailed descriptions of Nakshatras, or lunar mansions. These Nakshatras, which are fixed star constellations that the Moon traverses during its monthly orbit, are key components of the sidereal zodiac system. The text discusses the division of the sky into 27 or 28 Nakshatras (the 28th Nakshatra being ‘hidden’). Each Nakshatra represents a segment of the ecliptic through which the Moon passes during its monthly cycle. These segments are fixed relative to the stars. These early divisions of the sky reflect the ancient Indian emphasis on fixed star positions, a hallmark of the sidereal zodiac.

The principles established in Vedanga Jyotisha influenced subsequent astronomical and astrological texts, leading to the more explicit development of the sidereal zodiac, or Nirayana system, which uses fixed stars as a reference point. Thus, Vedanga Jyotisha played a crucial role in its evolution by establishing the importance of celestial observations and Nakshatras, ultimately laying the groundwork for the sidereal zodiac system in Indian astrology.

The Nakshatras form the basis of the sidereal zodiac system in Vedic astrology (Jyotisha), which aligns the 12 signs of the zodiac with these fixed star positions. This differs from the tropical zodiac used in Western astrology, which is based on the position of the Sun at the vernal equinox and is not fixed to the stars.

Nakshatras: The Eternal Language of the Stars

Meaning and Origin of Nakshatra

Nakshatras, known as lunar mansions, hold a significant place in Vedic astrology and astronomy. In classical Sanskrit, the word nakshatra is believed to be composed of two parts: na meaning “not” and kshatra meaning “destruction.” This etymological interpretation suggests something eternal or indestructible, highlighting the everlasting nature of the stars and constellations.

The term “nakshatra,” literally translating to “that which does not decay,” embodies the concept of an eternal, indestructible truth that does not erode with the passage of time. These lunar mansions are the bedrock of the sidereal zodiac, anchoring it to the immutable positions of the stars. The sidereal zodiac remains eternally accurate, unaffected by the passage of time.

This contrasts sharply with the tropical zodiac, which, once accurate, has been eroded by time as it no longer aligns with the constellations.

The term “nakshatra” can also be seen as a combination of naksha, meaning map, and tara, which means star.

In Vedic astrology, each nakshatra represents a cluster of fixed stars, covering 13° 20′ of the ecliptic – the distance the Moon travels in a single day. Each zodiac sign, or rashi, contains 2¼ nakshatras.

The sidereal zodiac, integral to ancient Vedic astrology, is deeply rooted in its fixed relationship with the stars or nakshatras. Unlike the tropical zodiac, which shifts with the equinoxes, the sidereal zodiac maintains an unchanging alignment with the celestial sphere, preserving the original positions of the stars as observed by ancient sages. This constancy allows the sidereal zodiac to serve as a timeless bridge to the divine realms, guiding the soul through its numerous lifetimes and fostering a sense of spiritual continuity amidst the ever-changing human experience.

The earliest mention of nakshatras can be traced back to the ancient Vedic texts, specifically the Rigveda, which dates around 1500 BCE. Ancient Indian astronomers identified and named these celestial markers by observing the moon’s journey through the night sky.

Each nakshatra is associated with a specific deity, imbuing it with unique characteristics and influences. These deities range from gods and goddesses to mythical sages and celestial beings, each governing the attributes and energies of their respective nakshatras.

The concept of Nakshatras offers a profound connection between the cosmos and human life, reflecting the notion that celestial patterns influence earthly experiences. Each nakshatra is not only a segment of the ecliptic but also a cosmic guide, revealing insights into one’s personality, destiny, and spiritual journey. This celestial mapping serves as a mirror, encouraging introspection and self-awareness, and offering a celestial framework for understanding one’s soul path.

The Vedic Luni-Solar Celestial Clock

The Vedic celestial clock, crafted through the intricate pattern of the Nakshatras, embodies a captivating blend of both solar and lunar cycles. At the heart of this system lies the Panchang, a cosmic calendar that meticulously tracks not only the phases of the moon but also the positions of the sun and other celestial bodies. Its brilliance is highlighted by the seamless integration of lunar and solar cycles, creating a harmonious calendar that guides the passage of time.

The Hindu calendar stands as a sophisticated framework, consisting of 12 lunar months. To maintain alignment with the solar year, an additional month, known as “adhik maas,” is occasionally inserted every 32-33 months. This ingenious system ensures the calendar remains synchronized with the solar year, reflecting the delicate balance between the sun and the moon’s cycles.

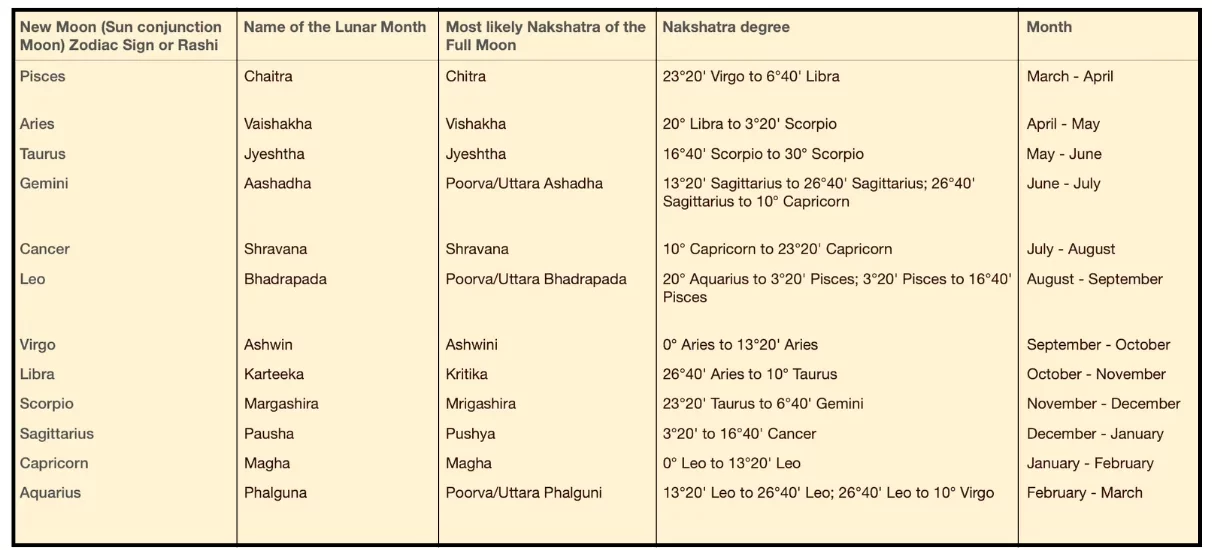

Each lunar month in the Hindu calendar begins with a new moon, and the months are named based on where the full moon typically appears in the sky. Specifically, the name of each month is linked to a Nakshatra, or lunar mansion, that the full moon usually aligns with during that time.

Chaitra and Vaishakha: Examples of Celestial Alignment

Chaitra: This month starts with a new moon in sidereal Pisces, occurring between March and April. It derives its name from the Chitra Nakshatra, which spans from late Virgo to early Libra. During Chaitra, the full moon usually aligns with the Chitra Nakshatra, marking its celestial significance.

Vaishakha: Following Chaitra, Vaishakha generally falls between April and May, beginning with a new moon in sidereal Aries. It is named after the Vishakha Nakshatra, which extends from late Libra to early Scorpio. The full moon during Vaishakha typically appears in the region of the Vishakha Nakshatra.

This naming pattern intricately connects each lunar month to its celestial counterpart, providing a unique rhythm that guides spiritual and cultural practices throughout the year.

One of the most brilliant aspects of the Panchang is its utility in guiding daily activities. It is consulted to determine the most auspicious times, or Muhurtas, for conducting important events such as weddings, religious ceremonies, business ventures, purchase of property or vehicles, and many more events. The Panchang helps individuals make informed decisions by aligning their actions with the cosmic rhythms, thereby maximizing the potential for success and harmony.

The Galactic Centre and Mula Nakshatra

One of the most significant points in Vedic astrology is the Galactic Centre, located in the Mula Nakshatra. Mula Nakshatra, one of the 27 lunar mansions, falls within the sign of Sagittarius. The Galactic Centre is a supermassive black hole at the center of our Milky Way galaxy, and its position in Mula Nakshatra is believed to hold profound spiritual and cosmic significance.

In Vedic astrology, Mula Nakshatra represents roots or source, and embodies the power of destruction and renewal. The Galactic Centre is often referred to as the “Source,” symbolizing the mind of God. The sidereal system maintains the relationship between Earth and the Galactic Center, the core of the Milky Way, ensuring that astrological readings remain connected to our galactic home. As the Earth revolves around the Sun and the Sun revolves around the Galactic Center, the Sidereal zodiac keeps us aligned with the fixed stars and the centre of our galaxy.

Padas and The Significance of 108

Each nakshatra is subdivided into four Padas (quarters), making a total of 108 Padas.

108 a number revered in many Eastern spiritual traditions. Astronomically, there is a fascinating relationship involving the Earth, the Moon, and the Sun. The average distance from the Earth to the Sun is about 108 times the diameter of the Sun, and similarly, the distance from the Earth to the Moon is approximately 108 times the diameter of the Moon.

In Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, 108 is considered a sacred number. It is often seen in the context of prayer beads or malas, which typically have 108 beads. These beads are used during meditation and chanting, allowing practitioners to focus their minds and count their mantras. The repetition of mantras 108 times is believed to help bring spiritual enlightenment and deepen one’s meditation practice. There are 108 Upanishads which are a collection of ancient Indian texts that delve into the nature of reality, the self, and the ultimate truth, often exploring concepts such as Brahman (the ultimate reality), Atman (the inner self or soul), and Moksha (liberation from the cycle of rebirth). The Upanishads are known for their profound metaphysical insights and are written in the form of dialogues, hymns, and philosophical discourses. Moreover, in some Eastern spiritual traditions, it is believed that there are 108 energy lines converging to form the heart chakra, one’s spiritual center. This convergence further emphasizes the holistic significance of 108 in connecting the physical, spiritual, and cosmic realms.

The Origin of the Zodiac Signs

Before embarking on a journey to explore the origins of the Zodiac signs, it is essential to first delve into the intricate realm of history and the hands that inscribe it. It is a realm where truths intertwine with biases, where facts dance with fictions, and where the pen often shapes the narrative to immortalize its wielder’s triumphs. As we navigate through the annals of time, the debate on the origins of the Zodiac finds itself entwined with the question of who writes history and how their accounts shape our understanding.

History and Who Writes It

Understanding that history or written records don’t always reflect the essential truth is crucial. History is woven from the threads of countless narratives, each coloured by the hand that records it.

For instance, the recognition of Hipparchus for the discovery of the precession of the equinoxes often raises questions about historical contributions from other civilizations. Indian astronomers were aware of this phenomenon and were using the sidereal zodiac long before Hipparchus’s time. The historical credit given to Hipparchus might be seen more as a reflection of the documentation and dissemination of his findings within Western scholarship, rather than a dismissal of similar knowledge in other cultures.

Recognizing the contributions of ancient Indian astronomers, along with those from other civilizations, provides a more comprehensive understanding of humanity’s collective advancements in astronomy.

Also worth noting, is that throughout history, the distortion of facts has been a significant subject of debate among scholars. Ironically, the title “Father of History” is commonly attributed to Herodotus, an ancient Greek historian also known as the “Father of Lies.” Herodotus is best known for his work “Histories.” While his accounts provide valuable insights into ancient cultures and events, they also contain numerous embellishments and inaccuracies. His descriptions of far-off lands and peoples, such as the gold-digging ants of India and the winged serpents of Arabia, often blur the line between fact and fiction.

These examples serve as a reminder that historical narratives can be skewed by the biases, misunderstandings, or even creative liberties of those who document them. Those with the pen may engrave their triumphs in stone, while the originators of the concepts have their tales fade into obscurity, overlooked by time.

The Invention and the Re-invention of the Zodiac Wheel

The origins and development of the zodiac signs have long been a topic of scholarly debate. While many attribute their invention to the Babylonians, a closer examination reveals that the foundations of these astronomical concepts lie in even older Vedic traditions. It is crucial to understand that the Babylonians should be credited with formalizing and documenting the zodiac rather than creating it. It’s similar to using a Tesla invention and giving credit to Edison.

Vedic astrology, believed to be as much as 5,000 years old, predates the earliest Babylonian records of the zodiac, which date back to around 700 BCE. This ancient Vedic system predates Babylonian astrology by several millennia, highlighting its deep-rooted heritage and significance in ancient Indian culture.

This situation is like reinventing the wheel, where the original invention is overshadowed by a later iteration—often with inferior results. The sidereal wheel, which demonstrates flawless accuracy to the stars, serves as a clear example of an optimized system, in comparison to the astronomically inaccurate tropical wheel.

Before being committed to writing, Vedic astrology thrived in oral tradition. The interaction between ancient civilizations facilitated the exchange of astronomical knowledge. Indus Valley seals found in Mesopotamia and Mesopotamian seals found in the Indus Valley are clear evidence of this exchange. The similarities in the zodiac signs used by both cultures further support this idea.

The original zodiac signs used by the Babylonians include the Hired Man, the Stars, the Twins, the Crab, the Lion, the Furrow, the Balance, the Scorpion, Pabilsag, the Goat-Fish, the Great One, and the Tails. While the Babylonians were instrumental in developing early astrological concepts, it’s important to note that some of their zodiac symbols differ significantly from the ones we recognize today. For instance, symbols like the Star, the Hired Man, and the Furrow illustrate this divergence.

Judging by these names, it’s clear that some information got lost in translation over time, much like the children’s game of ‘Chinese whispers.’ It is likely that the Babylonians encountered the concept of zodiac signs through trade and cultural exchanges with Indus Valley Civilization. While they successfully adopted many aspects, they also made some errors. One notable inaccuracy was their lack of awareness of the precession of the equinoxes, a phenomenon well-known to Indian astronomers. This oversight led to the development of the tropical zodiac, which ultimately became astronomically inaccurate over time. This example highlights the idea that while the Babylonians had a significant amount of knowledge, incomplete understanding can sometimes lead to misconceptions.

The Babylonians left extensive written records that have been crucial in tracing the history of the zodiac. Their cuneiform tablets document the division of the sky into 12 equal parts, a system that has significantly influenced modern astrology.

While the Babylonians played a significant role in formalizing and documenting the zodiac, it is essential to recognize that the intellectual origins of the zodiac signs are deeply rooted in Vedic astrology.

The Rig Veda, one of the oldest known scriptures in human history, contains references to the division of the celestial ‘wheel’ into twelve parts. Specifically, Rig Veda, Mandala 1, Hymn 164, Verse 11, discusses the division of the sky in a manner that parallels the later zodiac system. Later in this chapter, we will delve into the exploration of this hymn from the Rig Veda, along with a few other profound hymns. These texts shed light on the early Vedic understanding of celestial phenomena and their impact on earthly events.

The zodiac signs are deeply intertwined with the Nakshatras, and we will explore a few examples of this connection in the following topic.

The Cinderella Effect: The Harmonious Union of Nakshatras and Zodiac Signs

The age-old question of “what came first, the chicken or the egg?” finds a cosmic parallel in the origins of the zodiac signs. While many credit the origin of zodiac signs to Babylonians, the connection between the Vedic nakshatras and the zodiac signs points to the primordial “cosmic egg” of the Vedic nakshatras.

Just as the chicken and egg are inextricably linked, the fruit of the zodiac signs is deeply rooted in the mythological seeds of the Nakshatras.

Each nakshatra has unique characteristics that are intimately connected to the corresponding zodiac sign, or rashi, in which they reside.

For instance, Rohini Nakshatra, known for its associations with beauty, fertility, and material abundance, resides in Taurus. Taurus, ruled by Venus, enhances these attributes, making Rohini a nakshatra that favors creativity, sensuality, and prosperity.

Magha Nakshatra, which is associated with royalty, leadership, and ancestral reverence, is firmly situated within the sign of Leo. Leo, ruled by the Sun, imbues Magha with its regal, authoritative, and noble qualities, making it a powerful nakshatra for those who seek to lead and inspire.

Similarly, the Ashwini Nakshatra, located in Aries, is imbued with the pioneering, energetic, and dynamic qualities of Mars, Aries’ ruling planet. This makes Ashwini a nakshatra associated with new beginnings, healing, and swift action.

Mrigashira Nakshatra, which straddles the signs of Taurus and Gemini, demonstrates the complexity and duality that can arise from such placements. Mrigashira is symbolized by a deer’s head and embodies qualities of curiosity, exploration, and a quest for knowledge. Taurus lends a sense of stability and sensuality to Mrigashira, while Gemini contributes intellectual agility and communicative prowess. This amalgamation fosters an inquisitive and adaptable nature, making individuals with prominent Mrigashira placements keen seekers of new experiences and knowledge, while also valuing comfort and beauty.

Revati Nakshatra, located in the sign of Pisces and symbolized by the fish, epitomizes the themes of spiritual liberation and transcendence. Pisces, ruled by Jupiter, amplifies Revati’s inherent qualities of compassion, selflessness, and spiritual wisdom. Individuals influenced by this nakshatra are often inclined towards humanitarian efforts and exhibit a profound sense of empathy and understanding. Revati’s energies promote the dissolution of ego and the quest for higher consciousness, establishing it as one of the most spiritually potent nakshatras.

Continuing with the exploration of nakshatras and their zodiac sign connections, Pushya Nakshatra, located in the sign of Cancer, is intrinsically linked to themes of nourishment and protection. Cancer, ruled by the Moon, embodies the nurturing and maternal qualities that are reflected in Pushya. This nakshatra is often associated with the cow, a symbol of sustenance and fertility in many cultures. Just as the cow provides milk, a vital source of nourishment, Pushya emphasizes caregiving, growth, and the sustenance of life. The divine mother Aditi, associated with Punarvasu Nakshatra, also falls within Cancer, reinforcing the themes of motherhood, protection, and the cyclical renewal of life.

Hasta Nakshatra, which resides in the sign of Virgo, epitomizes skill, dexterity, and perfection. Virgo, an earth sign ruled by Mercury, is known for its analytical and meticulous nature. Hasta, symbolized by a hand, signifies manual dexterity and the ability to manifest ideas into reality through skillful actions. This nakshatra encourages individuals to strive for excellence in their crafts, promoting a sense of discipline and precision.

Similarly, Chitra Nakshatra straddles the cusp between Virgo and Libra. Symbolized by a shining jewel or pearl, Chitra represents the pursuit of brilliance and perfection. The Virgo influence enhances Chitra’s emphasis on beauty, artistry, and craftsmanship, infusing it with a meticulous and detail-oriented approach. As Chitra transitions into Libra, an air sign ruled by Venus, it gains an additional focus on harmony, balance, and aesthetic appeal. This combination makes Chitra a nakshatra that values creativity, refined talent, and the pursuit of artistic excellence.

Vishakha Nakshatra, straddling the signs of Libra and Scorpio, embodies the duality and choices associated with its symbolism of a two-forked branch. Libra, ruled by Venus, brings themes of balance, harmony, and indecision, while Scorpio, ruled by Mars, introduces intensity, transformation, and determination. This dual influence creates a dynamic tension within Vishakha, highlighting the challenges of making choices and navigating life’s crossroads. Individuals influenced by Vishakha often experience a push and pull between maintaining equilibrium and embracing change, making it a nakshatra that fosters growth through decisive action and the resolution of inner conflicts.

Anuradha Nakshatra, lying entirely in Scorpio, is symbolized by a lotus, signifying purity and spiritual awakening amidst adversity. Scorpio’s transformative energy enhances Anuradha’s themes of devotion, resilience, and the pursuit of higher truths.

These are just a few examples that illustrate the intimate connections between the nakshatras and the zodiac signs. The intricate web of associations extends far beyond what we have explored here, weaving together mythologies, deities, and the very essence of celestial bodies. Each nakshatra’s unique characteristics and its relationship with the zodiac sign(s) it resides in create a rich blend that highlights the depth and complexity of this ancient system.

These connections are not merely coincidental but rather a profound alignment, much like Cinderella’s glass slippers fitting her feet with unparalleled perfection. Together, the nakshatras and zodiac signs are not two disparate entities but a harmonious pair of cosmic glass slippers that belong together. Just as Cinderella not only had the glass slipper fit her foot perfectly but also had the other slipper to complete the pair, the nakshatras and zodiac signs complement each other in a balanced and intrinsically linked system. This dual relationship highlights the idea that one cannot fully comprehend the depths of the zodiac without acknowledging its roots in nakshatra mythology. This elegant union speaks to an ancient truth, one that predates and outshines any written records.

Ayanamsha

Ayanamsha is a critical concept in Vedic astrology, referring to the angular difference between the tropical (Sayana) and sidereal (Nirayana) zodiacs due to the precession of the equinoxes. The term “Ayanamsha” is derived from Sanskrit, where ‘Ayana’ means movement and ‘Amsha’ means part or portion.

An equation to derive the Nirayana (sidereal) zodiac from the Sayana (tropical) zodiac can be expressed as follows:

Nirayana (Sidereal) Position = Sayana (Tropical) Position – Ayanamsha

Several ayanamshas are in use, each with its own methodologies and rationale for calculation. Among these, the most popular is the Lahiri Ayanamsha, which has been standardized by the Government of India and is widely embraced for its accuracy and reliability.

For the year 2025, the Lahiri Ayanamsha is approximately 24°12’. Despite the differences in approach, most major ayanamshas typically remain within a few degree of each other. This results in only slight variations in the calculated positions of celestial bodies.

The Precession Puzzle: Why several Ayanamshas?

One might wonder why there isn’t just one ayanamsha with a universally fixed value. The reason lies in the dynamic nature of the celestial sphere and the historical and cultural contexts in which these ayanamshas were developed. Each ayanamsha represents a distinct approach to accounting for the precession of the equinoxes, reflecting diverse astronomical models and interpretations passed down through generations. This variety allows astrologers to choose a system that aligns with their philosophical beliefs and empirical observations, while also accommodating the gradual shifts and nuances in astronomical calculations over time.

0 Degrees Aries: Its Importance and Fluidity

The point of 0 degrees Aries holds immense significance in both Western and Vedic astrology, marking the commencement of the zodiac. However, unlike fixed stars, this point is not rigidly set in the sky due to the precession of the equinoxes, which causes a gradual shift in its position over time. This movement necessitates an ongoing recalibration of the zodiac, highlighting the importance of selecting an appropriate ayanamsha to accurately reflect the celestial framework.

If we imagine that the point of 0 degrees Aries was marked by a bright fixed star in the sky, it would make understanding the positions of all celestial bodies much simpler. Picture a clear night where you can easily see this shining star. If 0 degrees Aries were as visible and unchanging as this star, astronomers could easily calculate where every planet and star is located in relation to it.

This is because, with a clear reference point, you could simply measure angles from that star to find out where everything else is positioned. For example, if you know that a planet is 30 degrees away from this star, you would be able to pinpoint its exact location in the sky without much guesswork. It would be like having a map with a big, bright “Aries Starts Here” sign, making navigation straightforward and intuitive.

However, because 0 degrees Aries is not fixed and changes its location over time due to the precession of the equinoxes, it becomes more complex. This shifting means that astrologers and astronomers have to continuously adjust their calculations to account for these changes. Each ayanamsha offers a different way to navigate this complexity, allowing for a variety of methods to keep track of celestial bodies as they move over the years. In essence, if 0 degrees Aries were as constant as a bright star, we’d have a much easier time understanding the dance of the cosmos!

Different Techniques/Rationale Behind Ayanamshas

Different ayanamshas are derived from varying techniques and rationales, each rooted in distinct historical and astronomical principles.

There are several methods and reference points used to calculate ayanamsha, leading to different values. Several ayanamshas are in use, each employing unique techniques, reference stars, epoch dates, and other factors, leading to slight variations in their calculations.

An epoch date is a specific point in time used as a reference. Different systems use different epochs. For example, the Lahiri Ayanamsha, widely accepted in Vedic astrology, uses 285 AD as its epoch when the two zodiacs roughly coincided.

Reference points are crucial in many fields, including navigation, physics, and astronomy, as they provide a stable baseline from which to measure and calculate other variables. In astronomy, for example, fixed stars allow astronomers to chart the movements of celestial bodies reliably and consistently.

The choice of reference stars is crucial in determining the variations in Ayanamsha. Different Ayanamshas use different reference stars to anchor the sidereal zodiac, leading to slight variations in the calculated positions of celestial bodies. The choice of reference stars is rooted in their historical significance and observational reliability. Different Ayanamshas utilize stars like Spica, Aldebaran, etc based on their enduring visibility and fixed positions, providing a consistent reference for celestial measurements. These stars have been easier to observe and track accurately over long periods, making them practical choices for establishing a fixed point.

One might wonder why stars in the Aries constellation itself are not used as reference stars.

First, the Aries constellation itself does not clearly mark the 0 degrees Aries point. Unlike the fixed stars such as Spica in the Virgo constellation or Aldebaran located in the constellation of Taurus, Aries lacks a prominent star that can serve as a precise reference. The constellation contains stars of relatively moderate brightness, making it difficult to identify a specific starting point within its boundaries.

Moreover, the precession of the equinoxes adds another layer of complexity. Consequently, the position of 0 degrees Aries changes slowly over time, making it a moving target rather than a fixed point in the sky.

Due to these issues, stars in the Aries constellation are not used as reference points for 0 degrees Aries. Instead, astronomers and astrologers rely on more stable and easily identifiable stars in other constellations.

Ayanamsha Variations: A Closer Look

Though numerous ayanamshas exist, each with its distinct methodology and historical context, only a select few are highlighted here to illuminate the subtle differences that define them. Each ayanamsha offers a unique approach to celestial calculations, influenced by its choice of reference stars, epoch dates, and the philosophical underpinnings that guide its creation.

By examining these prominent ayanamshas, we can appreciate the diversity and depth of astrological thought that has evolved over centuries, as well as the diligent efforts of astrologers to determine and calculate the accurate positions of celestial bodies through meticulous observation and mathematical precision.

- Lahiri Ayanamsha

Named after its inventor, astronomer N.C. Lahiri, this ayanamsha is the most widely used and was standardized by the Government of India. It uses the fixed star Spica (Chitra) in the constellation Virgo as a reference point. The longitudinal difference between the tropical and sidereal positions of Spica is calculated and applied to determine the sidereal positions of planets and other celestial points.- Current Ayanamsha Value (as of June 1, 2025): 24°12’

- Raman Ayanamsha

Developed by the noted Indian astrologer B.V. Raman, this ayanamsha also utilizes Spica as its reference point. However, the epoch and calculation methods differ from those of the Lahiri Ayanamsha. The epoch date for the Raman Ayanamsha is set around 1000 A.D., resulting in a slight difference in the position of planetary bodies compared to Lahiri.- Current Ayanamsha Value (as of June 1, 2025): 22°45’

- Fagan-Bradley Ayanamsha

Named after Western astrologers Donald A. Bradley and Cyril Fagan, this ayanamsha emphasizes the fixed star Aldebaran, located in the constellation Taurus, as it offers precise alignment with ancient Babylonian and Egyptian star charts.- Epoch Date: Approximately 221 A.D.

- Current Ayanamsha Value (as of June 1, 2025): 25°05’

- Revati Ayanamsha

This ayanamsha uses the star Revati (Zeta Piscium) in the constellation Pisces. Revati is significant in Vedic astrology and provides an alternative method for calculating celestial positions.- Current Ayanamsha Value (as of June 1, 2025): 20°23’

- Hipparchus Ayanamsha

Named after the ancient Greek astronomer Hipparchus, this ayanamsha uses the star Regulus (Alpha Leonis) in the constellation Leo, historically associated with royalty and leadership.- Epoch Date: Around 127 B.C. (during the time of Hipparchus)

- Current Ayanamsha Value (as of June 1, 2025): 20°36’

- The Krishnamurti Ayanamsha

The Krishnamurti Ayanamsha is a unique system used in Vedic astrology to account for the precession of the equinoxes that distinguishes it from other systems. Unlike ayanamshas that rely primarily on fixed stars for reference, the Krishnamurti Ayanamsha incorporates a dynamic approach centered around the positions and interactions of planets within the zodiac. This involves the use of the Krishnamurti Paddhati (KP) system, which utilizes a series of sub-lords and emphasizes the intricate relationships between planets, signs, and houses. The KP system is known for its precision in predictions, attributed to its detailed consideration of planetary movements and influences. The Krishnamurti Ayanamsha is generally within the same range as the Lahiri Ayanamsha, which is approximately 24°07’ degrees as of June 1, 2025.

Sidereal vs. Tropical: A Cosmic Address Dilemma

When it comes to the eternal debate between the sidereal and tropical zodiacs, think of it like house hunting in the cosmos. Tropical zodiac supporters often pride themselves on its apparent clarity, pointing out that there’s no disagreement over where 0 degrees Aries starts. They argue that while Vedic or sidereal astrologers can’t seem to agree on the exact starting point of Aries due to multiple ayanamshas, at least tropical astrologers avoid this uncertainty.

However, this confidence is like proudly proclaiming you’ve found your way home, only to discover you’re in the wrong neighbourhood! The tropical GPS has led them to the wrong neighbourhood entirely—0 degrees Aries parked in the Pisces constellation.

While the sidereal zodiac might feel like searching for the right floor in an expansive cosmic building, we can rest assured that we’re at least at the correct address in the right celestial framework, in the right astral zip code. Remember: it’s better to be in the right building, even if unsure of the exact floor, than to wander around in a completely different neighbourhood!

Surrendering to the Mystery

Determining the exact value of Ayanamsha presents a profound challenge for astronomers and astrologers. Much like the precise values of Pi and the Golden Ratio, which cannot be fully captured by finite calculations, their pursuit often feels like chasing an elusive shadow. This endeavor hints at a deeper, mystical science that transcends our conventional understanding.

Throughout history, countless mathematicians have endeavored to calculate the exact value of pi (π), a mathematical constant representing the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter. Pi is an irrational number with digits stretching on forever.

The golden ratio, often denoted by the Greek letter phi (φ) is a mathematical constant that is, like pi, irrational. Its presence is witnessed in the spirals of galaxies like our Milky Way, as well as in the microcosm of seashells and the branching of trees. This ratio contributes to aesthetically pleasing proportions in art, architecture, and nature, illustrating the hidden depths of the cosmos from macro to micro scales.

Similarly, ayanamsha, which measures the shifting of celestial coordinates over millennia, defies precise calculation due to the subtle and continuous movement of the Earth’s axis.

This elusive nature suggests that these constants reflect the universe’s inherent mystery, revealing glimpses of divine intricacies at play. In many ways, the pursuit of understanding ayanamsha, pi, and the golden ratio serves as a metaphor for humanity’s quest to comprehend the cosmos.

While our tools of logic and mathematics have brought us far, there remains an ineffable quality to the universe that hints at a grand design beyond our reach.

Astrology is a spiritual science where the mystical intertwines with the logical, inviting us to embrace both our analytical minds and our sense of wonder. It reminds us that some truths may be God’s secrets, waiting to be uncovered not just through calculation but through a harmonious blend of reason and reverence for the mystery that surrounds us.

As we delve deeper into the mysteries of the universe, we are called to honour both the known and the unknown, recognizing that our journey toward understanding is as infinite and profound as the universe itself.

Ancient Indian Texts on Astrology

Vedanga Jyotisha and Rig Veda

The formal documentation of Vedic astrology began with the composition of the ancient texts known as the “Vedanga Jyotisha,” which dates back to approximately 1200 to 1000 BCE. These texts are considered some of the earliest known written records that systematically outline the principles of Vedic astrology. The Vedanga Jyotisha is part of the “Vedangas,” which are six auxiliary disciplines associated with the Vedas. The sections within the Vedanga Jyotisha provided detailed guidelines on the calculation of planetary movements and their influences, marking a significant shift from oral tradition to written documentation.

However, the roots of astronomical knowledge in ancient India can be traced even further back to the Rig Veda, one of the oldest sacred texts known to humanity, composed around 1500 BCE or earlier.

Remarkably, the Rig Veda contains numerous hymns that not only reference the cyclic nature of time, seasonal changes, and celestial phenomena like eclipses but also reveal a profound understanding of the heliocentric model of the solar system. These hymns depict the sun as the central force around which the other celestial bodies revolve, showcasing an advanced comprehension of the universe.

In essence, the hymn also aligns with concept of the Big Bang Theory, where the universe expanded from a singular point, ultimately giving rise to all celestial bodies, including planets formed from the remnants of the Sun. This connection emphasizes the Sun not only as the central entity of our solar system but also as a source from which life and matter emerged.

Additionally, the Rig Veda demonstrates an intricate knowledge of timekeeping and calendar systems. It presents the division of the sky into twelve parts, corresponding to the twelve months of the year, and introduces the concept of a seven-day week. This sophisticated approach to time division reflects the Vedic sages’ keen observational skills and their ability to systematically categorize and understand temporal cycles.

These early astronomical insights laid a foundational layer of knowledge that later texts like the Vedanga Jyotisha would build upon. The Rig Veda’s hymns not only serve as a testament to the advanced observational skills and intellectual achievements of ancient Indian scholars but also highlight the deep and enduring connection between spirituality and science in Vedic culture.

Hymn on Heliocentricity and The Big Bang Theory

Rig Veda, Mandala 1, Hymn 115, Verse 1

Sanskrit:

सूर्य आत्मा जगतस्तस्थुषश्च||

Transliteration:

Sūrya ātmā jagatas tasthuṣaś ca ||

Translation:

“The Sun is the soul of all that moves and is stationary.”

Meaning: This verse suggests a profound insight into the understanding of the heliocentric model, where the Sun is recognized as the central entity around which all planets revolve. It positions the Sun as not only a central force but also as the essence of the universe, mirroring the idea that from the cosmic explosion of the Big Bang, all planetary bodies—including Earth—were formed, with the Sun serving as a vital source of energy and life, reflecting an advanced comprehension of both heliocentricity and the origin of the cosmos.

Hymn on Seven Days of the Week

Rig Veda 1.50.8 (Hymn to the Sun):

Sanskrit:

स॒प्त त्वा॑ ह॒रितो॒ रथे॒ वह॑न्ति देव सूर्य । शो॒चिष्के॑शं विचक्षण ॥

सप्त त्वा हरितो रथे वहन्ति देव सूर्य । शोचिष्केशं विचक्षण ॥

Transliteration: sapta tvā harito rathe vahanti deva sūrya | śociṣkeśaṃ vicakṣaṇa ||

Translation:

“And seven horses, O Surya, carry you all over, with your golden flaming hair, in your chariot, O God, seeing wide!”

“The Sun, shining with great brilliance, moves with his chariot drawn by seven horses.”

Meaning: This hymn is an acknowledgment of the sun’s movement across the sky and the division of time into days. The reference to the chariot drawn by seven horses symbolizes the seven days of the week, indicating a sophisticated understanding of time measurement.

The seven horses that draw the Sun’s chariot in the Rig Veda hold deep symbolic meanings, connecting the natural and spiritual worlds. They also represent the seven colours of the rainbow—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet—which emerge when sunlight interacts with raindrops, symbolizing the diversity and unity within creation.

This highlights the Sun’s role as the source of all colours, showcasing its power to illuminate and beautify the world. Additionally, these horses symbolize the seven chakras, or energy centres, within the human body. Aligned along the spine, these chakras correspond to different levels of consciousness and spiritual awakening. The Sun’s chariot moving across the sky signifies the flow of energy through these chakras, promoting harmony and enlightenment

Hymn on Dividing the ‘Wheel’ into Twelve Parts and Marking the Year in Twelve Months

Rig Veda, Mandala 1, Hymn 164, Verse 11

Sanskrit:

“द्वादशारं नहि तज्जराय वर्वर्ति चक्रम्परि द्यामृतस्य |

अघ्निरत्रिं स्वधया सप्तसिंहैः समिद्धो अद्य मिथुनासो अर्यः ||”

Translation:

“The twelve-spoked wheel of time does not age, revolving around the heaven of truth. O Agni, your children, the paired ones, are here, seven hundred and twenty in number.”

Explanation:

Twelve-spoked wheel (dvādaśāraṃ cakram): This symbolizes the cycle of time, with the twelve spokes representing the twelve months of the year.

Does not age (nahi taj jarāya varvarti): This indicates the eternal and unchanging nature of time.

Revolving around the heaven of truth (pari dyām ṛtasya): This suggests the cosmic order (ṛta) and its perpetual motion.

Children of Agni (putrā agne): Agni, the fire god, is often associated with various divine entities or elements. Here, it refers to the days and nights as his ‘children.’

Paired ones (mithunāso): This refers to the pairs of day and night.

Seven hundred and twenty (sapta śatāni viṃśatiś ca): This number represents the total days and nights in a lunar-solar year, symbolizing a complete cycle.

Meaning: The hymn from the Rig Veda beautifully encapsulates the eternal cycle of time through the metaphor of a twelve-spoked wheel. This wheel represents the twelve months of the year, each spoke signifying one month, thereby dividing the sky into twelve distinct parts. The imagery of the wheel conveys the idea that time, much like the seasons, is cyclical and perpetually in motion. The phrase “does not age” highlights the timeless and immutable nature of this cycle, emphasizing that while individual moments may come and go, the overarching structure of time remains constant and eternal.

The hymn also speaks to the profound cosmic order, referred to as ṛta, which governs the universe. By describing the wheel as revolving around “the heaven of truth,” the text suggests that time is intricately linked to the universal order and truth. This order is not random but is governed by principles that maintain cosmic balance and harmony. The perpetual motion of the wheel around this heaven emphasizes the unceasing and reliable progression of time, reinforcing the concept of an orderly and predictable universe.

Agni, the fire god, is a central figure in Vedic literature and is depicted here as the progenitor of days and nights, referred to as his ‘children.’ The hymn mentions “seven hundred and twenty” paired entities, which correspond to the days and nights in a year. This number, 720, represents the total days and nights in a lunar-solar cycle, effectively symbolizing a complete year when both lunar and solar phases are considered.

A lunar year, which consists of 354 days, is based on the cycles of the Moon’s phases, while a solar year, at 366 days, is based on the Earth’s revolution around the Sun, including a leap year. To find the average length of these two types of years, we can simply add the number of days in each and then divide by two.

First, let’s calculate the sum of the days:

354 days (lunar year) + 366 days (solar year) = 720 days.

Next, we find the average by dividing this sum by two:

720 days / 2 = 360 days.

Thus, the average length of a year when considering both the lunar and solar measurements is 360 days. This average is quite close to the 365-day calendar year commonly used today, reflecting an interesting balance between the lunar and solar cycles.

Brihat Parashara Hora Shastra

Another crucial text on Vedic astrology is the “Brihat Parashara Hora Shastra,” attributed to the Sage Parashara. Although the exact date of its composition is uncertain, it is believed to have been written between the 5th and 6th centuries CE.

The Brihat Parashara Hora Shastra is one of the most revered classical texts in Vedic astrology. This comprehensive work delves into various aspects of Jyotish Shastra (Vedic astrology), offering detailed insights into planetary influences, astrological calculations, and predictive techniques.

One of the major components of the Brihat Parashara Hora Shastra is its in-depth discussion on the twelve zodiac signs (Rashis) and their characteristics. Each sign is described in terms of its qualities, ruling planet, and influence on human behavior and destiny. The text also elaborates on the significance of the twelve houses (Bhavas) in a horoscope, explaining how they represent different areas of life, such as career, wealth, and relationships.

One of the major components of the Brihat Parashara Hora Shastra is its in-depth discussion on the twelve zodiac signs (Rashis) and their characteristics. Each sign is described in terms of its qualities, ruling planet, and influence on human behavior and destiny. The text also elaborates on the significance of the twelve houses (Bhavas) in a horoscope, explaining how they represent different areas of life, such as career, wealth, and relationships.

Another crucial element of the Brihat Parashara Hora Shastra is its treatment of the nine planets (Navagrahas), including the Sun, Moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, Saturn, and the two lunar nodes known as chhaya grahas or shadow planets, Rahu and Ketu. The text details the effects of these planets when placed in different signs and houses, as well as their interactions through aspects and conjunctions. Additionally, it provides guidelines on the calculation and interpretation of planetary periods (Dashas), which are essential for making long-term predictions.

The Brihat Parashara Hora Shastra also covers a variety of other topics, such as yogas (planetary combinations that produce specific results), divisional charts (Vargas) for finer astrological analysis, and remedial measures to mitigate negative planetary influences. Overall, this seminal work serves as a foundational reference for practicing astrologers, offering timeless wisdom and practical techniques for understanding and predicting life’s events.

The Ethical Foundations of Astrological Knowledge

Chapter 1 – The Creation, Verses 5-8

In Brihat Parashara Hora Shastra, Chapter 1 – The Creation, Verses 5-8 lay out the essential ethical and spiritual qualities required for both the teacher and the student in the pursuit of astrological wisdom. This revered text highlights the profound nature of astrology and the importance of maintaining its sanctity through the transmission process.

Mahārśi Parāśara responded to a query, recognizing its auspicious purpose for the welfare of the Universe. In his response, he begins by invoking Lord Brahma, the creator deity, and Śrī Saraswati, Brahma’s consort and the goddess of knowledge and wisdom, alongside the Sun, the leader of the planets and the cause of Creation.

Mahārśi Parāśara answered. “O Brahmin, your query has an auspicious purpose in it for the welfare of the Universe. Praying to Lord Brahma and Śrī Saraswatī, his power (and consort) and Sun, the leader of the Planets and the cause of Creation, I shall proceed to narrate to you the science of Jyotishya, as heard through Lord Brahma. Only good will follow the teaching of this Vedic Science to the students, who are peacefully disposed, who honour the preceptors (and elders), who speak only truth and who are God-fearing. Woeful forever, doubtlessly, will it be to impart knowledge of this science to an unwilling student, to a heterodox and to a crafty person.”

The hymn emphasizes the ethical and spiritual prerequisites for both the teacher and the student in the transmission of astrological knowledge. It highlights the importance of moral integrity, respect, and a peaceful disposition as fundamental qualities for those who wish to learn this revered science. Essentially, the hymn suggests that astrology, being a sacred and profound discipline, should only be shared with individuals who possess certain virtuous characteristics.

Firstly, the hymn highlights that students who are peacefully disposed and honour their preceptors and elders are suitable recipients of this knowledge. This implies that a calm and respectful attitude is crucial for the proper comprehension and application of astrological teachings. Respect for teachers and elders is seen as a sign of humility and recognition of the wisdom that precedes one’s own understanding. Such students are likely to approach the science with the reverence it deserves, ensuring that the knowledge is used ethically and responsibly.

On the contrary, the hymn warns of the negative consequences of imparting this knowledge to those who are unwilling, heterodox, or crafty. An unwilling student, who lacks genuine interest or respect for the subject, may misuse or misunderstand the teachings, leading to detrimental outcomes. Similarly, a heterodox individual, who holds beliefs that deviate significantly from the established traditional norms, might distort the teachings to fit their own agenda. Lastly, a crafty person, driven by deceit or selfish motives, could exploit the knowledge for personal gain, undermining the sacred nature of astrology.

In essence, the hymn from the Brihat Parashara Hora Shastra serves as a guiding principle for the ethical transmission of astrological knowledge. It calls for teachers to be discerning and to ensure that their students embody virtues such as truthfulness, humility, and respect. By doing so, the sanctity of astrology is preserved, and its benefits can be fully realized by those who are worthy and prepared to receive it.

The Sidereal Zodiac: The True Foundation of Vedic Astrology

Vedic astrology must exclusively utilize the sidereal zodiac. Sometimes, new students accustomed to Western tropical astrology may inadvertently apply the incorrect tropical zodiac. However, those who possess a thorough understanding of both systems must never use the tropical zodiac for Vedic astrology, nor should they mislead others into doing so. Such actions contradict and violate the core principles of Vedic astrology.

The Sanctity of the Sidereal Zodiac

Using the tropical zodiac in Vedic astrology is not only incorrect but also viewed by many Vedic astrologers as heresy. Practitioners who hold the sanctity of Jyotish in high regard see this practice as a departure from its authentic foundations. The sidereal zodiac, grounded in the fixed positions of the stars, is the true reflection of Vedic astrology’s principles, offering an unerring connection to the celestial spheres.

The sidereal zodiac maintains the accuracy, integrity, and enduring wisdom of ancient Vedic astrology, faithfully mirroring the true celestial order. It offers a timeless framework, untainted by temporal changes, providing insights that are as relevant today as they were millennia ago.

To recap, the term “nakshatra,” literally translating to “that which does not decay,” embodies the concept of an eternal, indestructible truth that does not erode with the passage of time. These lunar mansions are the bedrock of the sidereal zodiac, anchoring it to the immutable positions of the stars. The sidereal zodiac remains eternally accurate, unaffected by the passage of time.

This contrasts sharply with the tropical zodiac, which, once accurate, has been eroded by time as it no longer aligns with the constellations.

Ethical and Spiritual Integrity

According to ancient texts like the Brihat Parashara Hora Shastra, the ethical and spiritual integrity of astrological knowledge is paramount. Any deviation from traditional practices disrupts this sanctity. The sidereal zodiac maintains its accuracy and integrity, firmly rooted in the nakshatras, which symbolize eternal, unchanging truths. In contrast, adopting the tropical zodiac disregards these ethical and spiritual prerequisites, potentially leading to misinterpretations and misuse of astrological wisdom.

Tradition and Innovation in Vedic Astrology

Tradition serves as a vital cornerstone in preserving the integrity and depth of practices like Vedic astrology. It provides a framework through which knowledge is transmitted, ensuring that the essence of ancient wisdom remains intact and continues to offer profound insights to those who seek it. By maintaining a steadfast commitment to traditional practices, practitioners honour the spiritual and ethical roots of Jyotish and safeguard its transformative potential for future generations.

In a rapidly evolving world, tradition acts as a stabilizing force, grounding us in a rich heritage while allowing us to navigate new paths with wisdom and reverence. Thus, to preserve the purity and insights of Vedic astrology, the sidereal zodiac must remain the sole foundation upon which it is built.

While tradition forms the bedrock of Vedic astrology, innovation also has its rightful place, particularly as modern astrological knowledge expands to include the outer planets—Uranus, Neptune, Pluto—and even asteroids. Many practitioners of Vedic astrology have embraced these celestial bodies, incorporating them into their interpretations without compromising the sanctity of the ancient practice. This inclusion represents a harmonious blend of time-honoured wisdom and contemporary insights, allowing astrologers to offer more nuanced readings that resonate with today’s complex world.

By integrating the discoveries of modern astronomy, such as the influence of outer planets, Vedic astrology enriches its understanding of the cosmos. This approach not only broadens the scope of Vedic astrology but also reinforces its relevance, ensuring that it remains a dynamic and evolving field. In this way, tradition and innovation work hand in hand, providing a holistic and insightful perspective on the celestial influences that shape our lives.